FMEA Must Not Be Used in Medical Device Design for Risk Evaluation Purposes

Introduction

In my consulting work with client companies, I have observed numerous cases where FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) is being employed in the design phase of medical device development. However, this practice requires significant clarification regarding its appropriate application within the medical device regulatory framework.

In my consulting work with client companies, I have observed numerous cases where FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) is being employed in the de…

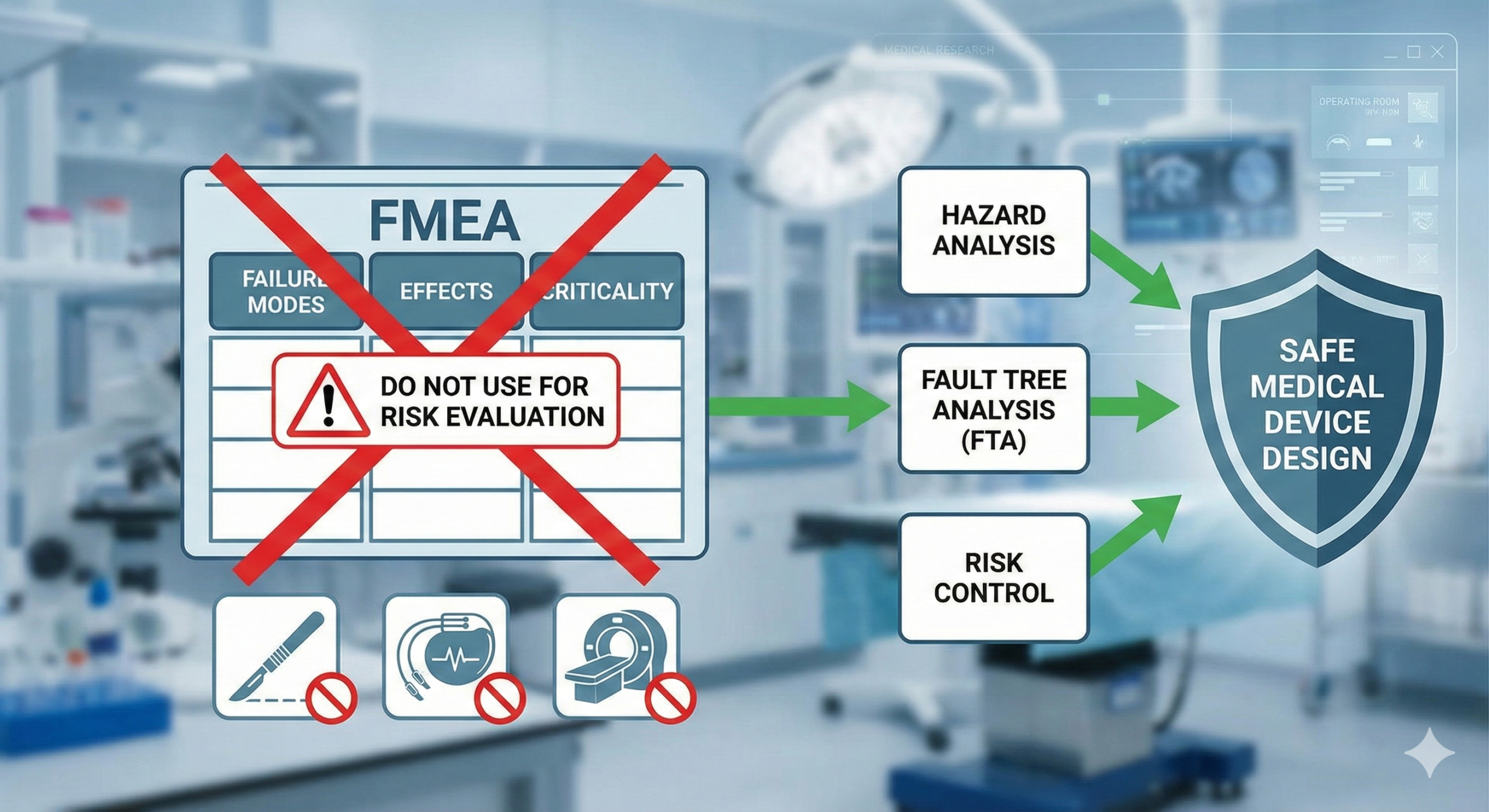

The critical point that requires emphasis is that FMEA, as defined in IEC 60812, is not referenced in medical device regulations such as Japan’s Basic Requirements Standard or the harmonized standards cited in the EU Medical Device Regulation (MDR). More importantly, the specific component of FMEA that incorporates “detectability” into risk prioritization is fundamentally inappropriate for medical device design risk management.

The Core Issue: Risk Priority Number (RPN) in FMEA

FMEA’s defining characteristic is that it combines risk with detectability to derive a metric called Risk Priority Number (RPN).

RPN (Risk Priority Number) = Probability of Harm × Severity × Detectability

In contrast, medical device risk management following ISO 14971 is based solely on:

Risk = Probability of Harm × Severity

This distinction is not merely academic—it represents a fundamental difference in how risk decisions are made for medical devices. Medical device risk management requires that risks be reduced to acceptable levels based on the severity and probability of harm, regardless of detectability. The detectability factor, which prioritizes economic considerations and manufacturing practicality, is irrelevant to patient and user safety.

To state this precisely: In medical device design, FMEA must not be used because its Risk Priority Number (RPN) incorporates detectability, which should not factor into design risk control decisions.

Detectability is relevant only in manufacturing and process control contexts, where it can support defect prevention measures. In design risk management, this logic is inverted and creates perverse incentives.

Practical Examples Demonstrating the Problem

To illustrate why RPN-based decision-making is inappropriate for device design, consider these two scenarios:

| Scenario | Severity (S) | Probability (P) | Detectability (D) | RPN | Risk (S×P) | Acceptable? |

| Case 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 120 | 15 | Yes |

| Case 2 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 63 | 21 | No |

Assume your company’s standards define: RPN < 100 = no risk control needed; Acceptable risk threshold = S×P < 20

Problem: Case 1 (RPN = 120) would be deemed to require risk control, while Case 2 (RPN = 63) would require none. However, the actual risk levels tell the opposite story:

- Case 1: S×P = 15, which falls within the acceptable range

- Case 2: S×P = 21, which exceeds the acceptable threshold

This paradox arises directly from the inclusion of detectability. In Case 1, high detectability artificially inflates the RPN despite low actual risk. In Case 2, low detectability artificially deflates the RPN despite unacceptable actual risk.

This inversion exemplifies why RPN-based prioritization fails in medical device design: it can lead to resources being allocated away from genuinely hazardous designs toward those with lower detection capabilities, regardless of actual patient harm probability.

Principle: Medical device design requires that risks be reduced to acceptable levels based on harm severity and occurrence probability, independent of any detection considerations. The fundamental obligation to ensure patient safety cannot be conditional on detectability.

Regulatory Basis for This Position

1. Japan’s Basic Requirements Standard (基本要件基準)

The Basic Requirements Standard, Section 2 (Risk Management), requires compliance with either JIS T 14971 or ISO 14971. The regulatory notification from the authority explicitly references these standards—never FMEA (IEC 60812). The silence regarding FMEA is significant: regulators do not state that FMEA is acceptable for design risk management.

2. ISO 14971:2007 Annex G (Superseded in 2019)

The 2007 edition of ISO 14971 included Annex G: “Information on risk management techniques.” This annex contained guidance on FMEA for the risk analysis stage (4.3) of the risk management process.

Key restriction from the original text:

“Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) and Failure Mode, Effects and Criticality Analysis (FMECA) are techniques for systematically identifying the effects or consequences of individual component failures. These techniques are best suited for use at stages where design is well-developed.”

Critical point: This guidance is explicitly limited to risk analysis (section 4.3) alone. The subsequent stages—particularly risk evaluation (4.4), where severity and probability are weighed—do not reference FMEA. Nowhere in the ISO 14971 standard does the guidance authorize the incorporation of detectability into risk control decisions.

This means FMEA may have limited utility in the risk analysis phase (for identifying failure scenarios and their consequences), but it provides no justification for using Risk Priority Numbers in risk evaluation or control.

3. ISO/TR 24971:2020 (Current Guidance Document)

Following the 2019 revision of ISO 14971, technical report ISO/TR 24971:2020 now serves as the authoritative guidance on risk management techniques. This document includes FMEA discussion in Annex B (informative): “Techniques to support risk analysis.”

The report provides this essential clarification:

“Risk analysis is merely one stage in the risk management process defined in JIS T 14971:2020. The techniques described in this annex do not address all elements of risk analysis and are merely supplementary. Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is a technique for systematically identifying and evaluating the effects or consequences of individual component failures. It is more suitable when design is well-developed and failure modes are well understood.”

Additionally, ISO/TR 24971:2020 section B.5 now includes an important restriction regarding detectability:

“FMEA may be expanded to integrate the findings of investigations into individual component failure modes, their probability of occurrence, detectability (limited in JIS T 14971:2020 to the extent that detection enables preventive measures), and the severity of consequences. To conduct FMEA, detailed knowledge of the medical device structure is necessary.”

This represents a critical nuance: The phrase “detectability (limited to the extent that detection enables preventive measures)” acknowledges a narrow exception for manufacturing and process contexts, as discussed below.

Where FMEA Does Have Legitimate Application

Having established why FMEA with RPN is inappropriate for device design, it is important to clarify where FMEA remains a valuable tool: in process and manufacturing design.

In manufacturing contexts, the logic changes fundamentally. When defects arise during production or assembly, the ability to detect those defects before they reach patients can prevent harm. In this scenario, detectability is directly relevant to risk reduction because detection enables preventive actions (defect removal) that interrupt the path to patient harm.

Manufacturing FMEA is appropriate because:

- Detectability directly supports preventive measures (defect sorting, rework, prevention systems)

- The manufacturer has direct control over detection and prevention mechanisms

- Detection acts as a necessary safeguard in the manufacturing and distribution chain

Design FMEA is inappropriate because:

- Detectability of a design defect does not prevent harm once the device reaches patients

- The patient cannot “detect and prevent” a hazardous design feature

- Risk mitigation must occur through design controls, not downstream detection

Summary and Recommendations

For medical device manufacturers, the guidance is clear:

In Design Risk Management: Follow ISO 14971 strictly. Conduct risk analysis using appropriate techniques (including, if helpful, FMEA’s structured approach to identifying failure modes and their consequences). However, base all risk evaluation and control decisions exclusively on risk = severity × probability. Do not incorporate detectability into design risk decisions.

In Manufacturing and Process Design: FMEA with appropriately scoped detectability evaluation can be a valuable tool for identifying process improvements, quality controls, and preventive measures that reduce the probability of manufacturing defects reaching patients.

Regulatory Alignment: Ensure your risk management documentation clearly references ISO 14971 (or JIS T 14971) rather than IEC 60812 (FMEA). If FMEA is used in any form, clearly distinguish between its application in process design versus its explicitly limited role in design risk analysis, and ensure no RPN-based decisions drive design risk control choices.

The ultimate principle remains: patient and user safety depends on reducing design risks to acceptable levels through design controls, independent of any considerations regarding detection or manufacturing practicality. This is the foundation of ISO 14971-compliant risk management and the underlying requirement of all medical device regulations globally.

Related Articles

- Why FMEA Should Not Be Used for Medical Device Design

- FMEA should not be used in medical device design

- Safe Design of Medical Devices: Understanding Risk Management Fundamentals

- Can GAMP Be Used in Medical Device Companies?

- Preventive Action as Risk Management: Understanding CAPA in Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Industries

- Understanding FMEA in Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Industries

Comment