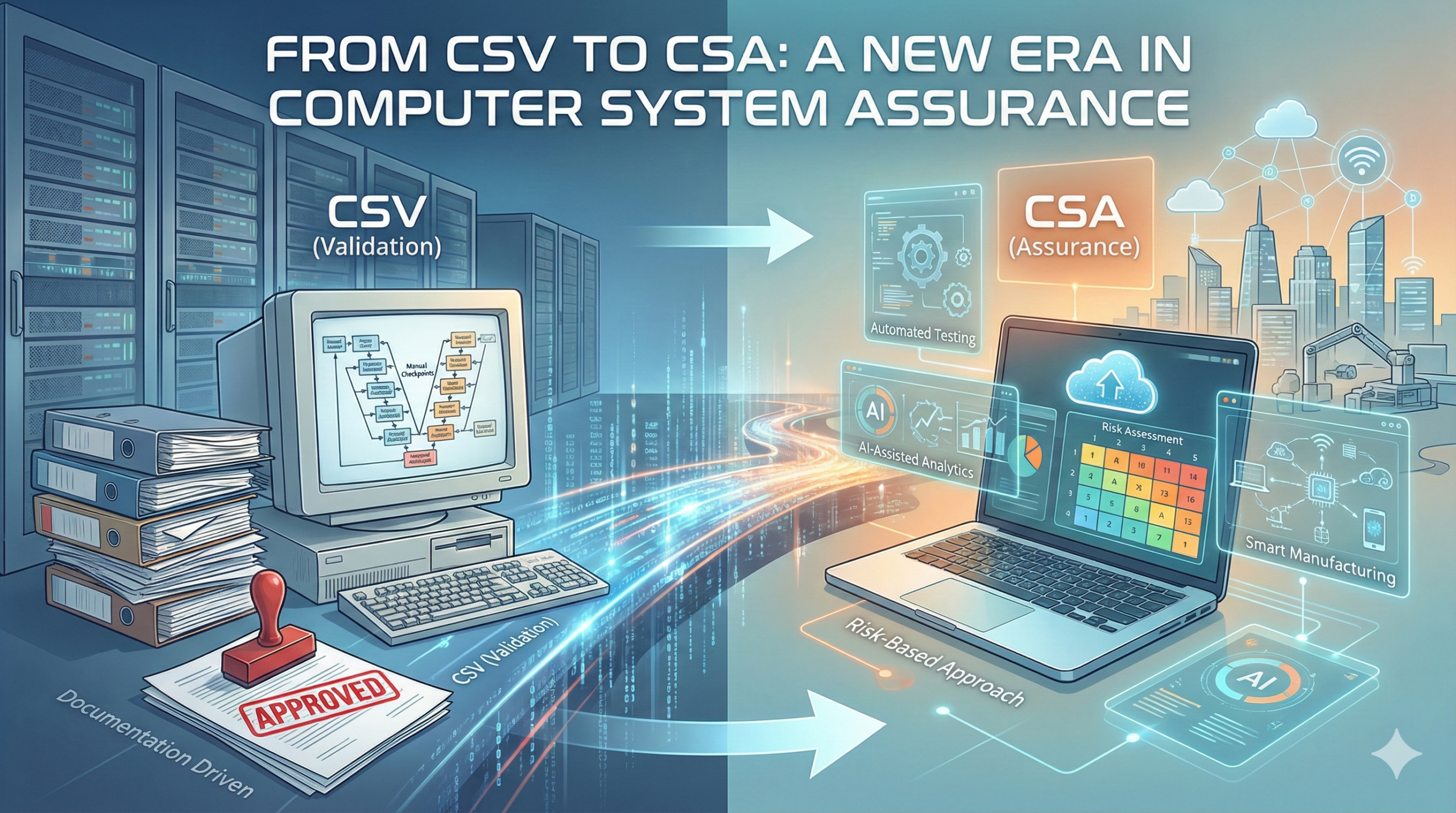

From CSV to CSA: A New Era in Computer System Assurance

FDA’s New Guidance Framework

The FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) is planning to release a new guidance document titled “Computer Software Assurance for Manufacturing, Operations and Quality Systems Software.” This represents a significant evolution in how the FDA approaches computer system validation and assurance across the pharmaceutical and medical device industries.

The FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) is planning to release a new guidance document titled “Computer Software Assurance for Man…

Although CDRH takes the lead in this initiative, the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), which oversees human pharmaceuticals, and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), which oversees biopharmaceutical products, are actively collaborating in its development. The International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE) GAMP working team is also contributing to the guidance development. This multi-stakeholder approach ensures that the resulting guidance will be applicable not only to medical devices but also to pharmaceuticals and biologics, creating a unified framework across the regulated industry.

The Context Behind Part 11 and System Validation

The pharmaceutical and medical device industries have been operating under 21 CFR Part 11, “Electronic Records; Electronic Signature,” which was implemented in 1997. This regulation established the requirement for Computerized System Validation (CSV) for companies managing electronic records and signatures.

The introduction of Part 11, while necessary for data integrity and regulatory compliance, created unintended consequences. Many pharmaceutical and medical device companies experienced delays in their digital transformation efforts or showed reluctance to update their computer systems due to the regulatory burden associated with CSV. The requirement for extensive documentation in CSV activities imposed significant resource demands—in terms of labor, cost, and time—on regulated companies. In contrast, other industries such as food and chemicals have leveraged IT modernization and automation to reduce costs and improve quality. In the pharmaceutical and medical device sectors, however, regulatory requirements have often created barriers to technological innovation rather than supporting it.

The new CSA guidance is expected to replace Part 11 as the FDA’s unified approach to computer systems, addressing these historical limitations while maintaining the fundamental principles of data integrity and regulatory compliance.

General Principles of Software Validation (GPSV): Scope and Limitations

The FDA issued “General Principles of Software Validation; Final Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff” (commonly referred to as GPSV) in January 2002. This guidance document provides principles for the validation of software used in the design, development, and manufacturing of medical devices and represents the FDA’s official stance on software validation practices. While the original version was published in 1987, it was substantially revised in 2002 following the implementation of the FDA’s Quality System Regulation (QSR) and Part 11 in 1997.

However, GPSV has a significant limitation in its applicability. The guidance provides detailed recommendations for validating product software—that is, software that is incorporated into or controls the medical device itself. Conversely, GPSV contains minimal guidance regarding non-product software—software used to support quality system functions such as enterprise resource planning systems, laboratory information management systems, document management systems, and other supporting infrastructure. This gap has been a driving factor in the development of the new Computer Software Assurance guidance.

The Paradigm Shift: From Validation to Assurance

Historically, the documentation requirements of CSV have often been driven more by the need to present evidence during audits and regulatory inspections than by genuine quality assurance objectives. This approach has created a situation where compliance costs borne by companies are ultimately passed through to healthcare systems and patients in the form of higher drug and device prices.

The new CSA guidance is designed to address these challenges by streamlining the documentation burden while maintaining rigorous quality assurance. The fundamental purpose of IT implementation and modernization should be to ensure patient safety, maintain data integrity (in accordance with ALCOA+ principles), and sustain product quality. The goal is not simply to present a convincing narrative to regulators during inspections.

Consequently, systems that have only indirect impacts on patient safety and product quality—such as employee training management systems—should not generate disproportionate documentation requirements. For example, there is no absolute requirement to develop detailed test scripts for every system function; rather, the critical activity is ensuring that test results are appropriately reviewed and documented. It remains a fundamental principle that if there is no documentation or record of an activity, it will be considered as not having been performed. Furthermore, traceability matrices that link requirements across documents continue to be essential. The art of the CSA approach lies in achieving this balance appropriately.

Scope of the New Computer Software Assurance Guidance

The new guidance applies to software used in manufacturing, measurement/analysis, and quality system operations for pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Quality system software encompasses systems such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) platforms, laboratory information management systems (LIMS), learning management systems (LMS), electronic document management systems (EDMS), and complaint/corrective and preventive action (CAPA) management systems. All such systems directly or indirectly support the quality and safety of the final product and therefore fall within the scope of the new guidance.

The Core of CSA: Critical Thinking

The new guidance incorporates the concept of critical thinking alongside the risk-based approach that the FDA articulated in 2003. This critical thinking methodology represents the philosophical foundation of the Computer Software Assurance approach.

Critical thinking, in the context of pharmaceutical and medical device regulation, means questioning underlying assumptions, challenging established norms, and examining the fundamental premises upon which practices are based. In many pharmaceutical and medical device organizations, compliance has become an end goal in itself rather than a means to an end. Many managers and employees organize their activities primarily around avoiding regulatory violations and preventing inspection findings. But what should the true objective be? The authentic goal should be to ensure patient safety by guaranteeing the quality of pharmaceutical and medical device products.

Quality assurance activities related to computer systems must be fundamentally aligned with this true objective. The practice of conducting exhaustive testing of every function and documenting every action may not generate meaningful value. How effectively can organizations challenge their established practices? How willingly can they question their underlying assumptions? These questions will test the entire industry as it transitions to the CSA paradigm.

Implementation of the Risk-Based Approach

The new guidance adopts a risk-based approach as its primary framework. The basic methodology involves analyzing the degree of risk that a particular computer system—or specific functions within a system—poses to patients, products, or quality system operations. This analysis results in a risk classification of High, Medium, or Low. The risk level then determines the appropriate quality assurance approach, with testing methodologies falling into one of three categories: Ad-Hoc, Unscripted, or Scripted testing.

In applying the risk-based approach, software is first classified into three categories based on the GAMP framework. Out of the Box (OOTB) software corresponds to GAMP Category 3—commercially available software used without modification. Configured software corresponds to GAMP Category 4—commercially available software that has been configured to meet organizational requirements without modification of source code. Custom software corresponds to GAMP Category 5—software developed specifically from source code to meet unique organizational needs.

The overall risk level is determined by combining the assessed risk to patients/products (High/Medium/Low) with the software category (3/4/5). This combined assessment determines which quality assurance activities are necessary:

| Risk Level | Quality Assurance Activities |

| 5 | Requirements validated through robust scripted testing |

| 4 | Requirements validated through limited scripted testing |

| 3 | Requirements validated through unscripted testing |

| 2 | Requirements validated through ad-hoc testing |

| 1 | Vendor audit and basic quality assurance activities |

This matrix ensures that the intensity of quality assurance effort is proportionate to the actual risk posed by each system, creating an efficient and scientifically defensible approach to computer system assurance.

The Transition from CSV to CSA: Challenges and Opportunities

The transition from the traditional CSV paradigm to Computer Software Assurance will present significant challenges. Organizations must abandon established practices and overcome the fear of receiving regulatory observations. Most importantly, the entire workforce must develop a genuine understanding of what quality assurance truly means and why it matters.

However, successful implementation of the CSA approach offers substantial benefits. When organizations genuinely improve product quality, the incidence of market complaints declines, and the time and resources spent on CAPA investigations and quality issues decrease correspondingly. Quality management and quality assurance departments may be able to optimize staffing levels as processes become more efficient and focused. Perhaps most importantly, the rate of adverse events and failures in marketed products will decline, resulting in safer and more reliable medical devices for patients and users.

The essence of the CSA approach represents a fundamental paradigm shift: moving from “compliance for compliance’s sake” to “quality assurance in service of patient safety and product quality.” Through this transformation, regulatory compliance and substantive quality improvement can be achieved simultaneously, creating a more sustainable and scientifically sound medical device and pharmaceutical industry.

Related Articles

- Understanding Assurance in Computer System Validation (CSV)

- From CSV to CSA: A Paradigm Shift in Computer System Validation

- Should Pharmaceutical Companies Be Responsible for Computer System Quality Assurance?

- FDA Issues Computer Software Assurance Guidance: A Paradigm Shift in Medical Device Quality Systems

- Understanding the True Purpose of Performance Qualification (PQ) in Computerized System Validation

- Risk-Based Approach in FDA Regulations: A Modern Framework for Computer System Validation

Comment