FDA Perspectives on CAPA Inspections

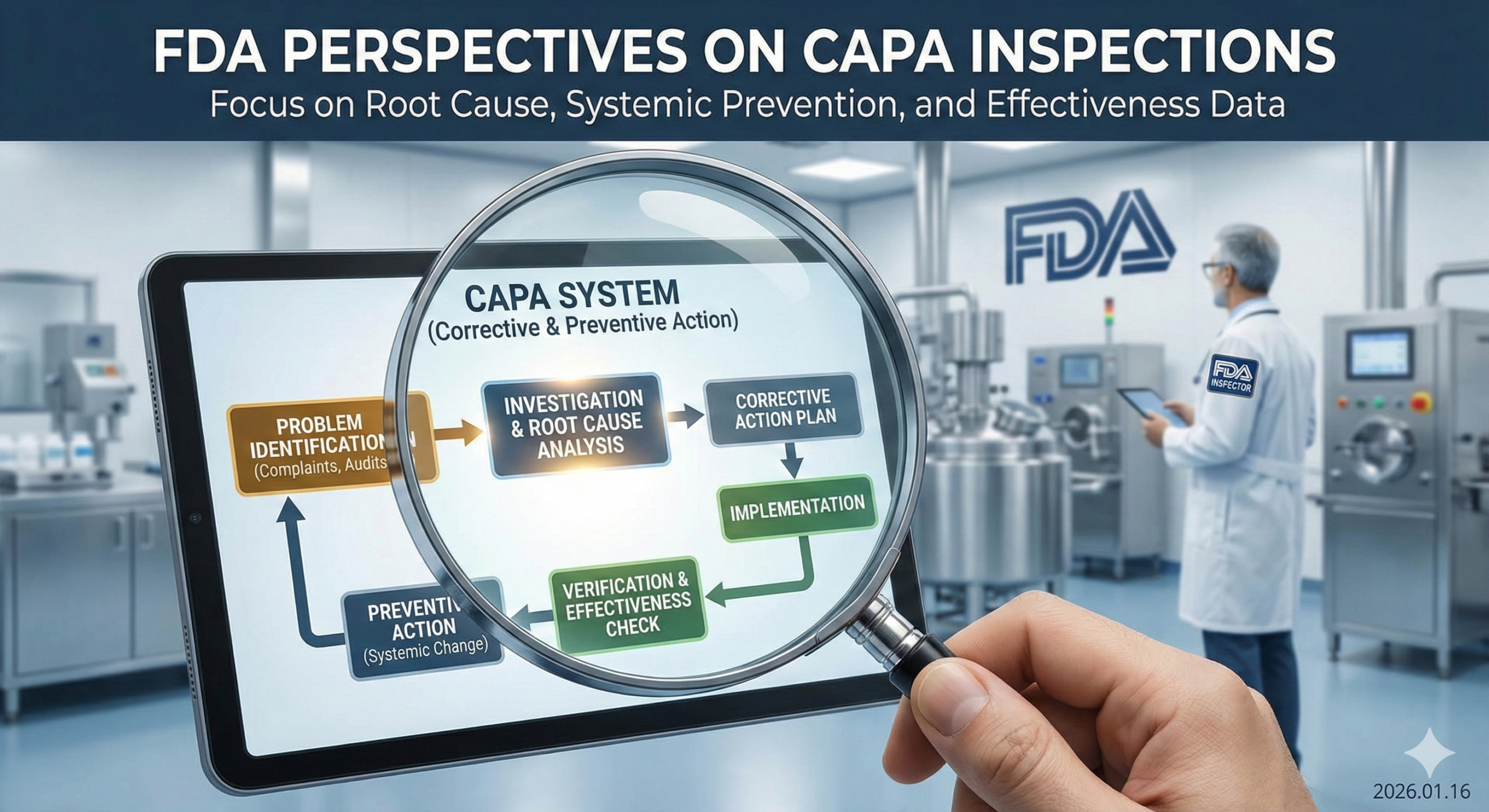

For companies manufacturing medical devices and pharmaceuticals, the Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) system forms the cornerstone of quality management. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) evaluates CAPA systems from specific perspectives during inspections. This article explains how the FDA inspects CAPA systems, focusing on their viewpoints and critical points.

What is CAPA?

CAPA is a systematic approach within quality systems to identify the causes of nonconformities or problems when they occur and prevent recurrence. “Corrective Action” addresses problems that have already occurred, while “Preventive Action” aims to prevent potential problems from arising. The FDA stipulates CAPA requirements in 21 CFR 820.100 (for medical devices) and 21 CFR 211 (for pharmaceuticals). These requirements also align with international standards such as ISO 13485:2016, which emphasizes risk-based approaches to quality management and continuous improvement through effective CAPA processes.

Key Perspectives in FDA Inspections

1. Identification and Documentation of Nonconformities

FDA investigators verify how companies identify and document nonconformities. They focus on the following aspects:

Methods for detecting nonconformities (complaints, audits, process monitoring, post-market surveillance data, etc.)

Companies should establish multiple channels for detecting quality issues. This includes not only traditional sources like customer complaints and internal audits but also proactive monitoring through statistical process control, supplier quality data, and post-market surveillance systems. The FDA expects companies to demonstrate that they actively seek out potential issues rather than waiting for problems to manifest.

Appropriate documentation of nonconformities

Each nonconformity must be documented with sufficient detail to enable thorough investigation. This includes the date and time of occurrence, description of the problem, affected products or lots, potential impact on patient safety, and initial assessment of severity. Documentation should be clear enough that someone unfamiliar with the situation can understand what occurred and why it matters.

Nonconformity severity assessment process

Companies must have a defined methodology for evaluating the severity of nonconformities. This typically involves assessing potential impact on product safety, efficacy, and regulatory compliance. The assessment should consider factors such as the likelihood of occurrence, detectability, and potential harm to patients. This risk-based approach helps prioritize CAPA activities and allocate resources effectively.

Implementation and utilization of trend analysis

The FDA expects companies to go beyond addressing individual nonconformities and identify patterns that may indicate systemic issues. Trend analysis should be performed regularly, using statistical methods where appropriate, to detect recurring problems, deteriorating processes, or emerging quality concerns. Companies should demonstrate that trend analysis results feed back into their CAPA system to drive preventive actions.

2. Adequacy of Root Cause Analysis

Investigators evaluate whether root cause analysis is appropriately conducted to identify the underlying causes of nonconformities.

Appropriateness of root cause analysis methods used (5 Whys, Fishbone Diagram, Failure Mode Effects Analysis, etc.)

The FDA does not mandate specific root cause analysis tools, but expects companies to select methods appropriate to the complexity and significance of the problem. Simple issues may be adequately addressed with the 5 Whys technique, while more complex problems may require advanced methods such as Fault Tree Analysis or Design of Experiments. Companies should demonstrate that they have trained personnel in these techniques and that the selected method is proportionate to the problem’s risk and complexity.

Depth and breadth of analysis

Superficial analysis is one of the most common CAPA deficiencies cited by the FDA. Investigators look for evidence that companies have thoroughly explored all potential contributing factors, including human factors, process design, equipment, materials, environment, and management systems. The analysis should extend beyond the immediate cause to identify underlying systemic issues.

Presence of objective evidence supporting root cause

Root cause determination should not be based solely on assumptions or opinions. The FDA expects companies to provide objective evidence—such as data, test results, observations, or measurements—that supports their conclusions about the root cause. This evidence-based approach ensures that corrective actions address actual problems rather than perceived ones.

Consideration of systemic issues

Individual failures often reflect broader systemic weaknesses. The FDA expects companies to consider whether identified root causes indicate problems with the quality management system itself, such as inadequate design controls, insufficient process validation, or gaps in training programs. This systemic perspective helps prevent similar problems across different products or processes.

3. Effectiveness of Corrective and Preventive Actions

The appropriateness and effectiveness of actions themselves are subject to focused inspection.

Whether actions address the root cause

This is perhaps the most critical aspect of CAPA effectiveness. Actions must directly address the identified root cause rather than merely treating symptoms. For example, if the root cause is an inadequate process design that allows errors, the corrective action should redesign the process to eliminate the error opportunity, not simply retrain operators or increase inspection.

Reasonableness of action implementation timeline

The FDA expects timely completion of CAPA activities, with timelines that reflect the risk and severity of the problem. High-risk issues require expedited action, while lower-risk issues may have longer timelines. However, all CAPA activities should have defined target completion dates, and any delays should be justified and documented. The FDA is particularly critical of CAPAs that remain open for extended periods without adequate justification.

Verification activities to confirm action completion

Companies must verify that planned actions have been actually implemented as intended. This may involve documentation review, process observations, testing, or other verification methods. The FDA looks for objective evidence that actions were completed, not just plans or intentions.

Consideration of impact on similar products or processes

When a problem is identified in one product or process, companies should evaluate whether similar issues could exist elsewhere. This “horizontal deployment” or “extent of condition” analysis demonstrates a proactive approach to quality management and helps prevent problems before they occur in other areas.

4. CAPA Effectiveness Verification

Investigators evaluate the process for confirming that implemented CAPAs actually solved the problem and prevented recurrence.

Methods and criteria for effectiveness verification

Effectiveness verification should be planned before actions are implemented, with clear, measurable criteria for success. The FDA expects companies to define specific metrics, acceptable ranges, and the duration of monitoring needed to confirm effectiveness. These criteria should be appropriate to the nature of the problem and the actions taken.

Objective evaluation based on data

Subjective assessments are insufficient for effectiveness verification. Companies must collect and analyze data that objectively demonstrates whether the problem has been resolved and recurrence prevented. This may include defect rates, process capability indices, complaint rates, audit findings, or other relevant metrics. The data collection period should be long enough to provide confidence in the results.

Long-term monitoring plan

Initial effectiveness verification is important, but the FDA also expects ongoing monitoring to ensure sustained effectiveness. Companies should have systems in place to detect if problems recur or if implemented actions become ineffective over time. This long-term perspective reflects a commitment to continuous improvement.

Procedures for responding when actions are ineffective

Not all corrective actions succeed on the first attempt. The FDA expects companies to have defined processes for identifying ineffective actions and taking additional steps. This may involve re-investigating the root cause, implementing alternative actions, or escalating the issue for management review.

5. Integration of CAPA Process

The FDA also verifies how the CAPA system is integrated with the overall quality system.

Coordination with other quality subsystems (change control, document management, supplier management, design controls, etc.)

CAPA should not function in isolation. When corrective actions require changes to procedures, specifications, or designs, these should flow through appropriate change control processes. When problems are traced to suppliers, supplier quality management processes should be engaged. The FDA looks for evidence of seamless integration across quality system elements.

Regular management review of CAPA

Senior management should demonstrate active engagement with the CAPA system through regular reviews. These reviews should assess CAPA metrics, evaluate the effectiveness of the overall system, identify trends, and allocate resources for improvement. Management review records should show that leaders understand quality issues and support necessary actions.

Utilization of CAPA data in quality metrics and KPIs

CAPA data provides valuable insights into quality system performance. Companies should incorporate CAPA metrics—such as the number of CAPAs opened/closed, time to completion, effectiveness rates, and types of root causes identified—into their quality dashboards and key performance indicators. These metrics help leadership understand quality trends and drive continuous improvement.

Evidence of continuous improvement

The ultimate goal of CAPA is not just compliance but continuous improvement of products, processes, and the quality system itself. The FDA looks for evidence that companies learn from their CAPA activities and proactively enhance their operations. This may be demonstrated through reduced defect rates, improved process capabilities, fewer customer complaints, or enhanced product performance.

Frequently Cited Deficiencies in Inspections

1. Insufficient Root Cause Analysis and the “Lack of Training” Problem

Many companies engage in superficial analysis and fail to identify the true root cause. The FDA repeatedly asks “why” and evaluates the depth of analysis. Approximately 15 years ago, the FDA began issuing citations when “lack of training” was identified as the root cause. This is because simply retraining the employee who made the error does not prevent the same problem from recurring when organizational changes or personnel transfers result in a different employee performing that process. The FDA emphasizes building robust processes and systems rather than systems dependent on individuals.

This policy reflects a fundamental principle of quality management: quality should be built into the system, not dependent on individual discipline or memory. When companies cite “lack of training” as a root cause, they are essentially admitting that their system relies on people not making mistakes, which is inherently unreliable. The FDA expects companies to ask deeper questions, such as:

- Why was the training inadequate to prevent this error?

- Why doesn’t the process design prevent or detect this error?

- Why is there no error-proofing mechanism?

- Why are written procedures unclear or difficult to follow?

- Why is there no independent verification step?

Acceptable approaches include redesigning processes to eliminate error opportunities (poka-yoke), implementing automated checks, creating clearer work instructions with visual aids, building in verification steps, or improving process monitoring to detect errors quickly. The focus should always be on system-level solutions that function reliably regardless of who performs the work.

2. Confusion Between Corrective and Preventive Actions

Many companies fail to distinguish between corrective actions (responses to problems that have already occurred) and preventive actions (prevention of similar problems) and do not implement both appropriately. The FDA expects both approaches to be clearly distinguished and documented.

Corrective actions address specific nonconformities that have already occurred. They focus on eliminating the cause of the detected problem to prevent recurrence. For example, if a manufacturing defect is discovered, the corrective action addresses why that specific defect occurred and ensures it doesn’t happen again.

Preventive actions are proactive measures to eliminate the causes of potential nonconformities before they occur. These are based on trend analysis, risk assessments, lessons learned from other products or processes, or industry best practices. For example, if trend analysis reveals a gradual increase in a process parameter that, while still within specifications, suggests a potential future problem, a preventive action would address this before any defect occurs.

The distinction is important because it demonstrates whether a company has a reactive or proactive quality culture. Companies with mature quality systems implement both types of actions as appropriate.

3. Lack of Timely Response

When CAPA completion is unreasonably delayed or prioritization is inappropriate, the FDA may issue warnings. Risk-based response deadlines must be established and adhered to.

The FDA recognizes that not all CAPAs can be completed immediately, but expects timelines to be commensurate with risk. High-risk issues affecting patient safety should be addressed urgently, potentially within days or weeks, while lower-risk issues may have longer timelines measured in months. However, even for lower-risk issues, companies should show steady progress rather than allowing CAPAs to languish indefinitely.

Common problems include CAPAs remaining open for years without justification, lack of interim actions while long-term solutions are developed, inadequate prioritization systems that allow high-risk issues to be treated as low priority, and failure to escalate when deadlines are missed or resources are insufficient.

4. Deficiencies in Document Management and Change Records

Issues frequently cited in FDA inspections include inadequate management of procedures and documents changed as a result of CAPA. Specific problems include:

Failure to record the names of procedures and documents changed by CAPA

Every CAPA that results in document changes should explicitly reference which documents were revised, including document numbers, titles, and revision levels. This creates a clear audit trail and ensures that all affected documents are identified.

Lack of records for employee notification (training records) regarding changed procedures

When procedures are revised, all affected employees must be trained on the changes before implementing the new procedure. Training records should document who was trained, when, on which document version, and that they demonstrated understanding. The FDA frequently cites companies for implementing procedural changes without training personnel, which can lead to confusion and errors.

Insufficient linkage between change management and CAPA systems

CAPA and change control are closely related but distinct processes. When CAPA activities result in changes, these should be processed through the formal change control system. The linkage between the two systems should be clear, with CAPA records referencing associated change control records and vice versa. This ensures proper evaluation of change impacts, approval by appropriate authorities, and validation where required.

Inadequate documentation of before/after document comparison and rationale for changes

Change documentation should clearly explain what changed and why. This may include revision summaries, redline versions showing specific changes, and rationale explaining how the changes address the CAPA root cause. This documentation helps with future troubleshooting and demonstrates that changes were thoughtfully implemented.

Such deficiencies may lead the FDA to determine that CAPA has not been properly completed and can result in Warning Letters. In severe cases, repeated documentation failures can contribute to consent decrees or other significant regulatory actions.

5. Insufficient Effectiveness Verification

Many companies fail to adequately evaluate CAPA effectiveness after implementation. The FDA requires objective data demonstrating that actions actually achieved their intended results.

Common deficiencies include conducting effectiveness verification too soon after implementation (before sufficient data can accumulate), using subjective rather than objective criteria, failing to define measurable success criteria in advance, not comparing post-implementation data to baseline data, and declaring effectiveness without supporting evidence.

Proper effectiveness verification should be planned upfront, with specific metrics, data collection methods, acceptance criteria, and timing defined. Data should be analyzed statistically where appropriate, and conclusions should be clearly supported by evidence.

6. Lack of Systemic Perspective

When companies address only individual problems without considering impacts on similar products or processes, the FDA identifies this as a weakness in the overall quality system.

This deficiency reflects a narrow, reactive approach to quality management. Mature quality systems recognize that problems rarely occur in complete isolation. If a particular failure mode has occurred, similar failure modes may exist elsewhere. If a process design issue caused a problem in one area, similar design issues may exist in related processes.

The FDA expects companies to routinely ask questions such as: Could this problem occur in similar products? Are other processes vulnerable to the same type of failure? What does this problem reveal about our design, validation, or supplier selection practices? Should we implement preventive actions more broadly?

This systemic perspective is particularly important for companies with multiple product lines, manufacturing sites, or related processes. Failure to consider the broader implications can result in repetitive problems and demonstrates an immature quality system.

Practical Advice for Successful CAPA Systems

1. Building Systems Not Dependent on Individuals

What the FDA emphasizes is not a system dependent on individual discipline or training but the establishment of a robust Quality Management System (QMS). Design and implement mechanisms that prevent problems from recurring even when personnel change.

This principle requires a fundamental shift in thinking from “preventing people from making mistakes” to “designing systems where mistakes are difficult to make or easy to detect.” Practical approaches include:

Error-proofing (poka-yoke): Design processes so that errors cannot occur or are immediately detected. Examples include physical guides that prevent incorrect assembly, software lockouts that prevent unauthorized actions, or automated checks that verify data integrity.

Process standardization: Develop clear, detailed procedures with visual aids, flowcharts, and examples. Standardization reduces variability and makes it easier for any qualified person to perform the work correctly.

Built-in verification: Include independent verification steps, peer reviews, or automated checks within processes rather than relying on individuals to catch their own errors.

Technology enablement: Use technology to enforce compliance, guide users through complex processes, and automatically detect deviations. This might include electronic batch records, automated process controls, or decision-support systems.

2. Risk-Based Approach

Rather than treating all nonconformities at the same level, prioritize based on risk and allocate resources appropriately.

Risk-based CAPA prioritization considers factors such as potential impact on patient safety, regulatory compliance implications, business impact, and likelihood of occurrence. High-risk issues receive immediate attention and more resources, while lower-risk issues may be addressed through routine improvement activities.

This approach aligns with FDA expectations and international standards like ISO 14971 for medical device risk management. It ensures that limited resources are focused where they matter most and demonstrates mature quality system thinking.

Companies should have documented procedures for risk assessment within their CAPA system, including defined criteria, decision matrices, and approval authorities for prioritization decisions.

3. Data-Driven Decision Making

Identify root causes and evaluate action effectiveness based on data rather than intuition or feeling.

The FDA expects objective, evidence-based decision making throughout the CAPA process. This includes using data to identify problems (trending, statistical analysis), investigate root causes (testing, experimentation, measurement), select appropriate actions (benchmarking, literature review), and verify effectiveness (comparative analysis, process capability studies).

Data-driven approaches reduce bias, enable better decisions, provide objective documentation for FDA inspection, and facilitate continuous improvement through quantitative assessment.

Companies should invest in data systems that enable effective collection, analysis, and visualization of quality data. This might include statistical process control software, quality management system databases, or business intelligence tools.

4. Cross-Functional Involvement

Involve various departments (Quality, Production, Engineering, Regulatory, etc.) in the CAPA process to ensure multi-faceted perspectives.

Complex quality problems rarely have simple solutions that fall within a single department’s domain. Effective CAPA requires input from multiple functional areas:

Quality: Provides expertise in quality systems, regulatory requirements, and investigation methods

Production/Operations: Offers practical insights into process realities and implementation challenges

Engineering: Contributes technical expertise in process design, equipment, and validation

Regulatory Affairs: Ensures compliance with applicable regulations and standards

R&D: Provides product design knowledge and technical development capabilities

Supply Chain: Addresses supplier-related issues and material quality

Cross-functional CAPA teams bring diverse perspectives that lead to more thorough root cause analysis, more innovative solutions, better implementation planning, and greater buy-in for changes. Companies should formalize cross-functional involvement in their CAPA procedures and ensure appropriate representation based on the nature of the problem.

5. Effective Documentation and Integration of Change Management

Clearly identify and record documents (procedures, work instructions, specifications, etc.) changed as a result of CAPA. Ensure that records of employee notification (training records) for changed documents are reliably maintained. Properly integrate change management and CAPA systems to ensure change traceability.

The following table summarizes key documentation requirements for effective CAPA/change management integration:

| Documentation Element | Requirements | Best Practices |

| CAPA to Change Linkage | CAPA record must reference associated change control numbers | Use bidirectional references; CAPA records link to changes, change records link back to originating CAPA |

| Document Identification | List all documents revised, including document number, title, and revision level | Create a “documents affected” section in CAPA records; use document management system integration where possible |

| Change Description | Document what changed and why (connection to root cause) | Include redline versions or change summaries; explain how changes address root cause |

| Training Requirements | Define who needs training on changes and when | Use role-based training matrices; require training completion before procedure effective date |

| Training Records | Document that affected personnel were trained on revised procedures | Include trainee name, date, trainer, document/revision trained on, and competency verification |

| Implementation Timing | Define when changes become effective | Coordinate implementation across all affected areas; avoid partial implementation |

| Verification of Implementation | Confirm changes were implemented as intended | Include verification step in change control; observe processes, review records |

Effective integration between CAPA and change management ensures that quality improvements are properly implemented, sustained, and documented in a manner that satisfies FDA expectations.

6. Process Standardization and Error-Proofing

Rather than simple retraining, perform process design that incorporates mechanisms making errors difficult to occur or detectable when they do occur.

This principle represents the core of FDA’s philosophy: building quality into the system rather than inspecting quality in or relying on human vigilance. Practical strategies include:

Visual management: Use color coding, labels, visual work instructions, and process indicators to make correct actions obvious and errors visible.

Standardized work: Develop detailed standard operating procedures with clear step-by-step instructions, decision criteria, and examples. Reduce ambiguity and variation.

Automation: Automate repetitive tasks, calculations, or checks where human error is likely. Use technology to enforce compliance and detect deviations.

Simplified processes: Reduce complexity where possible. Fewer steps mean fewer opportunities for error. Combine or eliminate unnecessary activities.

Physical constraints: Use fixtures, guides, or equipment design to make incorrect actions impossible. For example, connectors that only fit one way, or containers that hold exactly the right amount.

Real-time feedback: Provide immediate feedback when errors occur rather than discovering them later through inspection. This enables quick correction and learning.

Redundancy and verification: Build in independent checks, peer reviews, or automated verification for critical steps.

The Role of Digital Technologies and Data Integrity

In recent years, the FDA has increased focus on data integrity within CAPA systems, particularly as companies adopt electronic quality management systems (eQMS) and other digital technologies.

Data integrity principles (often referred to as ALCOA+: Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available) apply fully to CAPA records. The FDA expects companies to ensure that electronic CAPA records are protected from unauthorized alteration, have complete audit trails showing who made changes and when, are backed up and recoverable, and are readily available for FDA review during inspections.

Benefits of electronic CAPA systems include improved traceability and audit trails, automated workflow management and notifications, better trend analysis and reporting capabilities, easier integration with other quality systems, and reduced risk of lost or incomplete paper records.

However, digital systems also introduce risks that must be managed, such as inadequate access controls, system validation deficiencies, incomplete audit trails, and data migration problems when systems are upgraded or replaced.

Companies implementing or operating electronic CAPA systems should ensure robust computer system validation per 21 CFR Part 11 and related FDA guidance, strong access controls and user authentication, comprehensive audit trails that cannot be disabled, regular data backups and disaster recovery testing, and data integrity monitoring and periodic review.

Current FDA Inspection Trends

Based on recent FDA inspections and published Warning Letters, several trends are evident:

Increased focus on CAPA effectiveness: The FDA is placing greater emphasis on whether CAPAs actually work, not just whether they are documented. Inspectors look for objective evidence of improved performance following CAPA implementation.

Heightened attention to repeat problems: When similar issues recur after CAPA implementation, this draws significant FDA scrutiny. Repeat problems suggest ineffective root cause analysis or inadequate actions.

Integration of post-market surveillance: The FDA expects CAPA systems to effectively incorporate post-market data, including complaint trends, adverse event reports, and field performance data. CAPAs should address patterns identified in post-market surveillance.

Scrutiny of supplier-related CAPAs: When problems are traced to suppliers, the FDA examines both the CAPA addressing the immediate issue and the company’s broader supplier quality management. Companies should demonstrate that supplier-related CAPAs consider whether similar problems could exist with other suppliers or materials.

Emphasis on management involvement: The FDA expects senior management to be actively engaged with the CAPA system, not just signing periodic reviews. Management should demonstrate understanding of key quality issues, provide adequate resources, and drive quality improvement.

International Harmonization and ISO 13485:2016

While this article focuses on FDA requirements, it’s important to note that CAPA expectations are increasingly harmonized internationally. ISO 13485:2016, the international standard for medical device quality management systems, includes specific requirements for corrective and preventive action that align closely with FDA expectations.

Key provisions of ISO 13485:2016 relevant to CAPA include:

Clause 8.5.2 (Corrective Action): Requires organizations to take action to eliminate the cause of nonconformities, review nonconformities, determine root causes, evaluate the need for action, implement needed action, review the effectiveness of corrective action, and update risks determined during risk management.

Clause 8.5.3 (Preventive Action): Requires determination of potential nonconformities and their causes, evaluation of the need for action to prevent occurrence, implementation of needed action, and review of effectiveness.

The standard emphasizes risk-based thinking throughout the quality management system, with CAPA serving as a key mechanism for managing quality risks.

Companies operating in global markets should design their CAPA systems to meet both FDA requirements and ISO 13485:2016, ensuring a single integrated system satisfies multiple regulatory frameworks. This approach reduces complexity, improves consistency, and facilitates regulatory inspections by multiple authorities.

Conclusion

FDA’s approach to CAPA inspection is not merely a compliance check but an evaluation of a company’s problem-solving capabilities and quality system maturity. What the FDA emphasizes is not dependence on “individual discipline” but building a robust QMS (Quality Management System) as a “mechanism.” This is the reason the FDA has taken a strict stance on root cause analysis citing “lack of training” for approximately 15 years.

An effective CAPA system not only meets regulatory requirements but also brings clear business benefits including improved product quality, increased customer satisfaction, and enhanced operational efficiency. The key to succeeding in FDA inspections while achieving long-term quality performance improvement lies in cultivating a truly preventive quality culture through initiatives such as system design not dependent on individuals, process standardization, and error-proofing.

Companies should view CAPA not as a burden but as an opportunity—an opportunity to learn from problems, strengthen processes, and build competitive advantage through superior quality. When integrated effectively with risk management, change control, and other quality system elements, CAPA becomes a powerful engine for continuous improvement that benefits patients, customers, and the business itself.

As regulatory expectations continue to evolve with increasing focus on data integrity, risk-based approaches, and systemic thinking, companies must continually enhance their CAPA systems. By embracing the principles outlined in this article—robust system design, data-driven decision making, cross-functional collaboration, and genuine commitment to quality improvement—organizations can build CAPA systems that not only satisfy FDA inspectors but genuinely enhance product quality and patient safety.

Comment