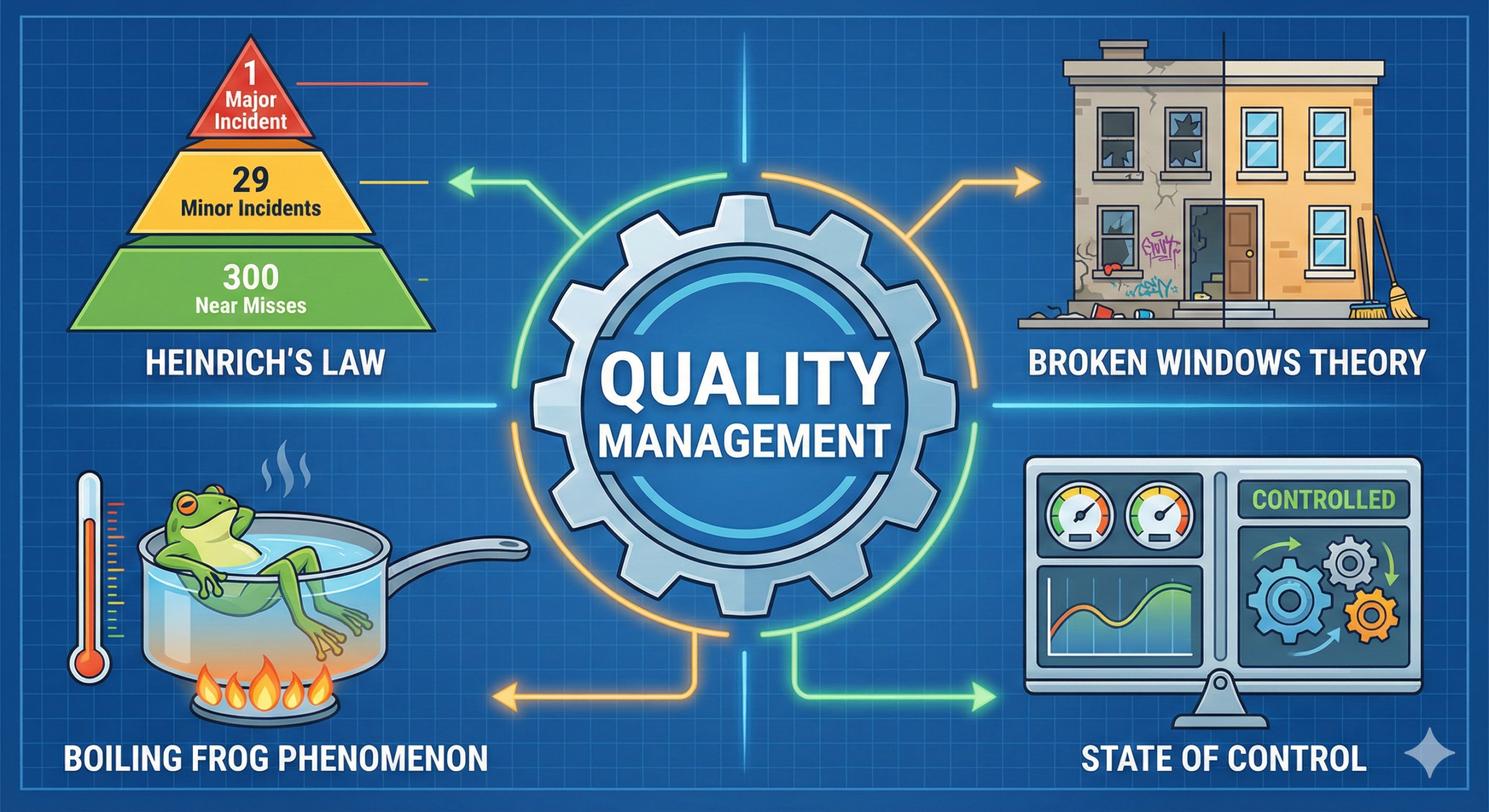

Quality Management Principles: Heinrich’s Law, Broken Windows Theory, Boiling Frog Phenomenon, and State of Control

Heinrich’s Law

When I conduct seminars on CAPA (Corrective Action and Preventive Action), I am frequently asked, “For what kinds of quality issues should CAPA be implemented?”

The answer is: for incidents that require recurrence prevention.

The purpose of CAPA is improvement, specifically recurrence prevention. Therefore, CAPA should be implemented when the impact on the quality of pharmaceutical products or medical devices is judged to be significant.

However, there is something called Heinrich’s Law. This law states that behind one major accident or disaster, there are 29 minor accidents or disasters, and behind those, there are 300 near-misses (incidents that did not result in accidents but were close calls). This is also known as the 1:29:300 Law.

If 300 minor near-misses are overlooked, they will eventually lead to 29 accidents. If 29 accidents are left unaddressed, they will lead to one major accident. This is the essence of the law.

It is important to note that while the 1:29:300 ratio originated from statistical data collected by Herbert William Heinrich in the United States around 1931, the specific numerical ratio is not as critical as the underlying principle. The key insight is that major accidents do not occur in isolation—they are preceded by numerous minor incidents and near-misses. This principle has been validated through various studies, including Frank Bird’s analysis (1:10:30:600 ratio) in 1969, which examined 1.75 million accident reports across 297 companies. What matters most in applying Heinrich’s Law is not adherence to specific numbers, but rather the recognition that a single major incident is invariably preceded by numerous smaller incidents and near-misses.

A Notable Case Study

There is one well-known example. In March 2004, a six-year-old boy was crushed to death by a revolving door at Roppongi Hills. According to reports, from the opening of Roppongi Hills in April 2003 until this fatal accident—a period of approximately one year—there were 32 reported incidents involving the revolving doors, with 7 of these involving children similar to the fatal case.

This is a clear manifestation of Heinrich’s Law. When it became apparent that minor accidents were occurring frequently, Roppongi Hills should have taken appropriate measures. By failing to address these warning signs, this was an accident that could and should have been prevented.

This case illustrates a critical failure in the application of quality management principles and risk management. The management had multiple opportunities to prevent the tragedy through proper analysis of incident trends and implementation of effective corrective actions.

Application to Quality Management

In other words, even if quality problems are minor, if they occur repeatedly, CAPA (improvement) must be implemented. To achieve this, information on recurring minor quality problems must be collected using statistical methods. For example, the same minor complaint is repeated three times in one month, or minor deviations are repeated three times in the same process.

Organizations should establish threshold criteria for triggering CAPA based on their risk assessment and quality management strategy. These thresholds should be documented and regularly reviewed as part of the quality management system. Modern quality management systems often employ trend analysis and statistical process control to detect patterns that may indicate systemic issues before they escalate into major problems.

Broken Windows Theory

The Broken Windows Theory is a theory that applies Heinrich’s Law. This theory was developed by criminologist George Kelling (working with political scientist James Q. Wilson) and published in 1982 in the Atlantic Monthly.

The theory is based on an experiment conducted by psychologist Philip Zimbardo at Stanford University in 1969. In a well-maintained residential area, a car was left with its hood open for one week, but nothing happened. However, when a car with a broken windshield was similarly left, its windows were broken one after another, and valuable parts were almost entirely stolen.

This demonstrates that if small crimes are left unaddressed, they will eventually lead to major crimes. This is a theory from criminal psychology that illustrates how environmental cues influence behavior.

The New York City Application

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani applied this theory to the New York City subway system. When graffiti in the subway was thoroughly removed, the number of serious crimes decreased dramatically. This “Zero Tolerance” policy, implemented starting in 1994, included thorough enforcement of minor offenses such as graffiti, shoplifting, illegal parking, jaywalking, and drunk driving. As a result, the city achieved significant reductions in crime rates, including a 68% decrease in murders over five years, demonstrating the practical effectiveness of the Broken Windows Theory in urban crime prevention.

Understanding the Psychological Mechanism

Small mistakes and negligence, when tolerated, cause people to lose their sense of guilt and become less resistant to making mistakes (habituation). Even if there is a sense of guilt, the psychology works where people rationalize their behavior, thinking “if this much is allowed, a little more should be okay” (rationalization).

Practical Application in Organizations

Supervisors should not scold subordinates for failures. Rather, they should appropriately point out small, trivial matters in a timely manner. For example, situations such as “trash was thrown toward a wastebasket but missed and fell on the floor and was left there,” or “documents stapled together were assembled crookedly.”

Activities such as “organizing one’s desk” and “cleaning” are taken for granted, but surprisingly, no one pays attention to them. The feeling that “it’s just this much” can eventually lead to major failures and losses.

In fact, my specialty of quality control and quality assurance follows the same philosophy. When small quality improvements are made, major mistakes (recalls due to defects) decrease. This principle is fundamental to modern quality management systems, where continuous improvement and attention to detail prevent systemic failures.

Boiling Frog Phenomenon

If a frog is suddenly placed in hot water, it will be startled and jump out, but if it is placed in room-temperature water and the temperature is gradually raised, it will miss the timing to escape and eventually die.

The Boiling Frog Phenomenon is used as a metaphor to illustrate the difficulty and importance of responding to slowly progressing environmental changes and crises. It is sometimes expressed as the “Boiling Frog Law” or “Boiling Frog Theory.”

It is certainly true that we are insensitive to slowly progressing environmental changes and crises. While procrastinating work, thinking “there’s still time,” we may find ourselves in an irreversible situation. Or we may continue to rely on gradually outdating skills and knowledge, avoiding learning, and end up being left behind by the times and losing our position within the company.

When we notice environmental changes or crises, we should make it a practice to deal with them immediately. In the pharmaceutical and medical device industries, this principle is particularly relevant given the rapid pace of technological advancement, evolving regulatory requirements, and changing healthcare paradigms. Organizations must remain vigilant and proactive in monitoring and responding to changes in their operational environment.

State of Control

The FDA frequently uses the term “State of Control.” This term is also used in ICH Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System).

From the lessons of Heinrich’s Law, the Broken Windows Theory, and the Boiling Frog Phenomenon described above, a company’s quality control and quality assurance must be maintained in a “state of control.”

In FDA inspections and similar regulatory assessments, it is investigated whether the company has established a quality system under the management’s policy and whether it is in a state of control.

Definition and Significance

According to ICH Q10, a state of control is achieved when the pharmaceutical quality system “assures that the desired product quality is routinely met, suitable process performance is achieved, that the set of controls are appropriate, that improvement opportunities are identified and evaluated, and that a state of control is maintained throughout the product lifecycle.”

This state is not static but dynamic, requiring continuous monitoring, evaluation, and improvement. A state of control encompasses:

- Process Performance: Manufacturing processes operate consistently within established parameters

- Product Quality: Products consistently meet specifications and quality attributes

- Control Strategy: Appropriate controls are in place based on product and process understanding

- Continuous Improvement: Systems are in place to identify and act on improvement opportunities

- Knowledge Management: Product and process knowledge is captured, maintained, and utilized effectively

Integration with Quality Management Principles

The concept of a state of control integrates all the principles discussed in this article:

- Like Heinrich’s Law, it emphasizes the importance of detecting and addressing minor deviations before they escalate

- Like the Broken Windows Theory, it recognizes that small lapses in control can signal and lead to larger quality issues

- Like the Boiling Frog Phenomenon, it requires vigilance against gradual degradation of quality standards

A company that maintains a state of control can be considered a reliable company. Such companies demonstrate maturity in their quality management systems, proactive risk management, and commitment to continuous improvement. This not only ensures patient safety and product quality but also provides competitive advantages through operational excellence and regulatory confidence.

Practical Implementation

To maintain a state of control, organizations should:

- Implement robust monitoring systems that track both process performance and product quality

- Establish effective CAPA systems that address deviations promptly and prevent recurrence

- Conduct regular management reviews to assess system effectiveness and drive improvement

- Apply quality risk management principles throughout the product lifecycle

- Foster a quality culture where every employee understands their role in maintaining control

- Utilize knowledge management to capture learning and continuously enhance understanding

By integrating these elements, pharmaceutical and medical device companies can establish and maintain the state of control necessary for sustainable success in highly regulated industries.

Comment