Why We Reduce Probability Rather Than Severity: The Fundamental Logic of Risk Control

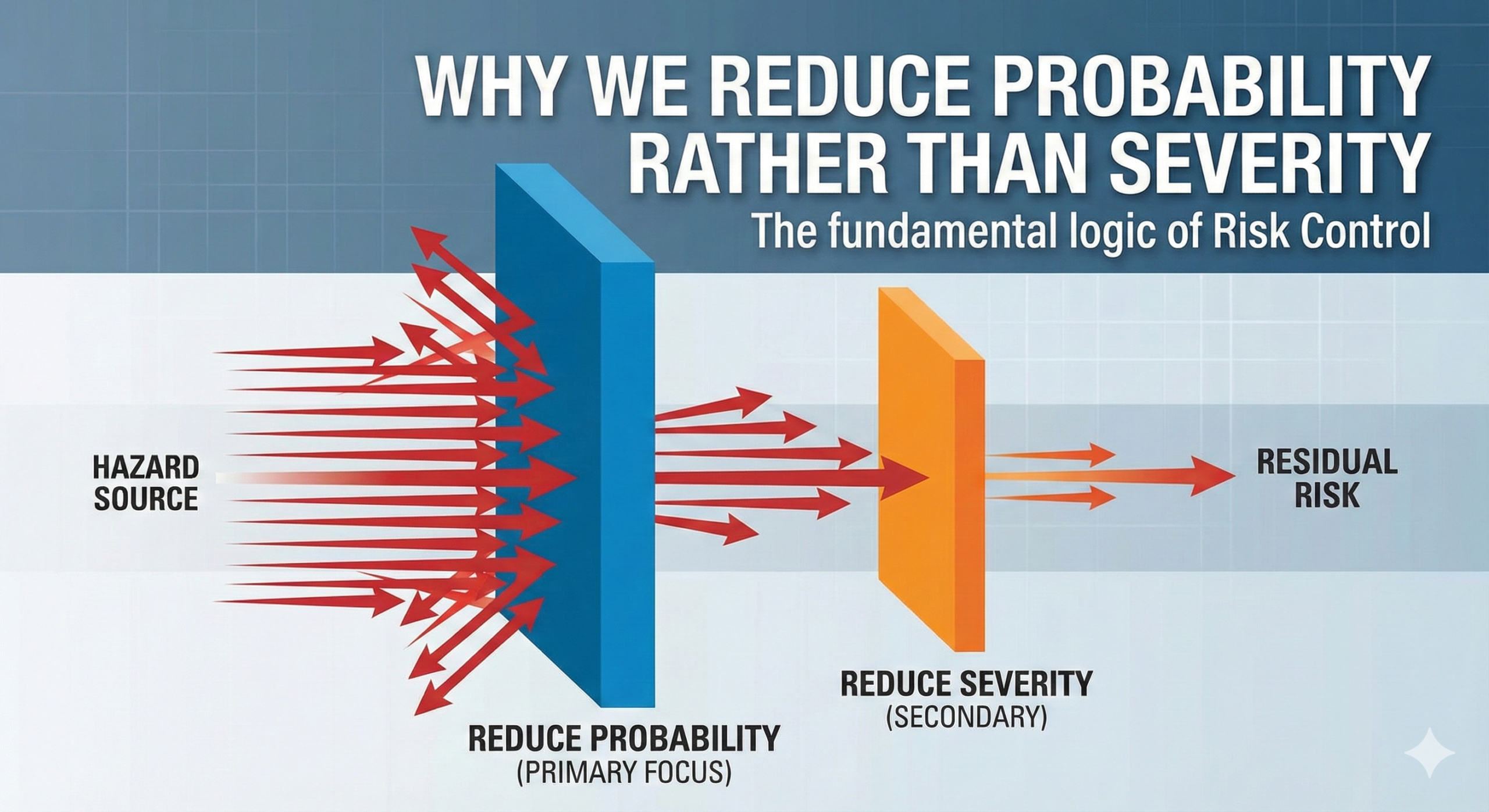

Anyone working in the field of risk management confronts a fundamental question: “Why is it difficult to reduce the severity of harm, and why do we focus on reducing the probability of occurrence?” Behind this seemingly simple question lies the essential philosophy of risk control.

Anyone working in the field of risk management confronts a fundamental question: “Why is it difficult to reduce the severity of harm, and why do we fo…

The Two Elements of Risk

When evaluating risk, we always consider two elements: “severity of harm” and “probability of occurrence.” Risk is determined by the combination of these two factors. This fundamental concept, formally defined in ISO 14971:2019, the international standard for risk management of medical devices, applies universally across industries and remains the cornerstone of systematic risk assessment.

Consider an aircraft accident, for example. The severity of a crash is extremely high. In most cases, it results in serious consequences involving the lives of crew members and passengers. This severity remains fundamentally unchanged regardless of technological advances. The physical impact of plummeting to the ground from an altitude of 10,000 meters is unavoidable.

Why Severity Cannot Be Reduced

The reason the severity of harm cannot be reduced is often rooted in physical laws and biological limitations. Creating an aircraft from which passengers would not die even in a crash is impossible with current technology. Similarly, for many hazards such as falls from height, contact with high voltage, and exposure to toxic substances, it is impossible to alter their inherent danger.

Of course, exceptional success stories do exist. The introduction of seat belts and airbags in automobiles is a rare example of actually reducing the severity of harm in collision accidents. These safety devices mitigate the actual damage sustained by occupants by dispersing and absorbing impact forces during a collision. However, such successful examples of severity reduction are extremely limited when viewed in the broader context.

According to ISO 14971, risk control measures follow a specific hierarchy of effectiveness. The standard prioritizes three levels of control in descending order: (1) inherent safety by design, (2) protective measures in the device or manufacturing process, and (3) information for safety such as labeling, warnings, and user training. This hierarchy reflects a practical reality: while design modifications may occasionally reduce severity, they more commonly address probability reduction.

Focus on Probability Reduction

Therefore, in practical risk control, the focus shifts to reducing the probability of occurrence. Creating “aircraft that extremely rarely crash” is entirely possible, as demonstrated by modern aviation technology. In fact, commercial aircraft accident rates have declined dramatically over the past several decades.

Methods for reducing probability are diverse. They include incorporating safety into the design phase, ensuring multiple layers of protection (redundancy), conducting regular maintenance, standardizing work procedures, thorough education and training, and designing interfaces that prevent human error. ISO 14971 emphasizes that manufacturers must systematically identify hazards throughout the device lifecycle and implement appropriate control measures based on the hierarchy mentioned above.

In the medical device industry, probability reduction is further reinforced by regulatory frameworks. The EU Medical Device Regulation (MDR 2017/745) and In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR 2017/746), along with FDA‘s Quality System Regulation (21 CFR 820), explicitly require manufacturers to demonstrate comprehensive risk management aligned with ISO 14971 principles. The FDA’s recent Quality Management System Regulation (QMSR, 2024) has further strengthened this alignment by explicitly incorporating risk-based principles throughout the product lifecycle.

Risk Acceptability

The goal of risk management is not to eliminate risk entirely, as that is practically impossible. Rather, the objective is to reduce risk to an “acceptable level.” This acceptability is determined through comprehensive consideration of social consensus, regulatory requirements, technical feasibility, and economic rationality. ISO 14971 requires manufacturers to establish predefined risk acceptability criteria during the risk management planning phase, typically represented through risk acceptance matrices that map severity against probability.

For example, in medical devices, the severity of harm to patients often cannot be changed. A surgical scalpel must be inherently sharp, and radiation therapy equipment must emit powerful radiation. For these devices, overall risk is maintained at an acceptable level by reducing the probability of harm occurring due to misuse or equipment failure to an absolute minimum.

The concept of “acceptable risk” as defined in ISO 14971 is inherently relative to the benefit the device provides. Life-saving devices for otherwise incurable conditions can tolerate higher residual risk than devices used for simpler applications. This benefit-risk analysis, explicitly required under both the EU MDR and ISO 14971:2019, has become a critical component of demonstrating regulatory compliance.

Implications for Practice

Engineers and managers engaged in risk control must deeply understand this fundamental principle. When designing new products or systems, it is important to begin with the question, “Is it truly possible to reduce the severity of this harm?” In most cases, however, the answer will be “no.”

At that point, our efforts should be directed toward reducing the probability of occurrence. We must employ all available means—fail-safe design, fool-proof design, preventive maintenance, monitoring system implementation—to minimize the possibility of harm occurring. This is the practical and effective form of risk control.

The hierarchy of risk controls established in ISO 14971 provides a systematic framework for this approach. First priority goes to inherent safety by design—eliminating or reducing hazards through fundamental design choices. Examples include using biocompatible materials, avoiding sharp edges that could puncture sterile barriers, or implementing bounded input ranges in software. Second priority involves protective measures such as safety guards, alarms, interlocks, and monitoring systems. Only when these measures prove insufficient does the focus shift to information for safety, recognizing it as the least reliable control method since it depends entirely on user behavior.

Verification and Post-Market Surveillance

A critical aspect often overlooked is the requirement to verify the effectiveness of implemented risk control measures. ISO 14971:2019 explicitly requires manufacturers to verify that each control measure has been properly implemented and that it effectively reduces risk as intended. This verification must include objective evidence such as test results, design validation data, or clinical evidence.

Furthermore, the 2019 revision of ISO 14971 significantly strengthened requirements for production and post-production information monitoring. Manufacturers must establish systematic processes to collect and analyze field data, customer complaints, adverse event reports, and emerging scientific literature to identify previously unrecognized hazards or situations where the frequency of harm differs from initial estimates. This closed-loop feedback mechanism ensures that risk management remains a living process throughout the entire product lifecycle, from initial design through post-market surveillance and eventual product retirement.

Modern regulatory frameworks increasingly emphasize this continuous monitoring. The FDA’s MAUDE (Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience) database and the EU’s EUDAMED system provide valuable sources of post-market data that manufacturers must systematically review to detect safety signals and assess whether their original probability estimates remain valid.

The Practical Reality

Risk management is a practical discipline that balances ideals with reality. While accepting the constraint that the severity of harm cannot be reduced, we must exercise creativity and ingenuity in reducing the probability of occurrence. This fundamental understanding leads to the realization of safer products and systems.

The table below summarizes the key differences in approach between severity reduction and probability reduction:

| Aspect | Severity Reduction | Probability Reduction |

| Feasibility | Often limited by physical laws and biological constraints | Generally achievable through systematic design and process controls |

| Typical Examples | Airbags, energy-absorbing materials, protective shielding | Redundant systems, preventive maintenance, fail-safe mechanisms, user interface improvements |

| Regulatory Preference | Encouraged when technically feasible | Primary focus of most risk control strategies |

| Control Hierarchy Position | Primarily through inherent safety by design | Addresses all three levels: inherent design, protective measures, and information for safety |

| Verification Method | Design validation, impact testing, clinical data | Reliability testing, failure rate analysis, post-market surveillance data |

In conclusion, the fundamental asymmetry between our ability to control severity versus probability is not a limitation to lament but rather a reality that guides us toward more effective risk management strategies. By concentrating resources on systematic probability reduction while remaining alert to rare opportunities for severity mitigation, we can achieve the goal of bringing safe, effective products to market while maintaining regulatory compliance and protecting patient safety. This pragmatic approach, codified in ISO 14971 and embraced by regulatory authorities worldwide, represents the state of the art in medical device risk management and provides a reliable pathway for engineers and quality professionals navigating the complex landscape of product safety.

Related Articles

- Severity Remains: ISO 14971’s Precise Framework for Understanding Risk Control and Residual Risk Assessment

- Why Focus on Residual Risk Rather Than Initial Risk?

- Why Focus on the Probability of Harm Rather Than the Probability of Defects?

- Why Software Safety Classes Can Be Reduced Through Other Risk Control Measures

- Why Severity Takes Precedence Over Frequency: A Practical Approach to Risk Control in Medical Devices

- Quality Control: Fundamental Concepts and Practical Application

Comment