Revisions to ISO 14971:2019 (Part 1)

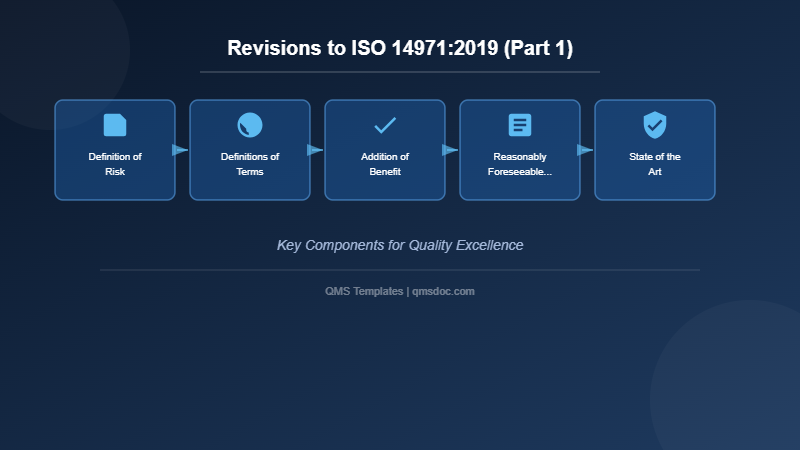

As previously discussed, ISO 14971 “Medical devices – Application of risk management to medical devices” has undergone significant revisions. This article provides a detailed explanation of the key changes introduced in this revision.

As previously discussed, ISO 14971 “Medical devices – Application of risk management to medical devices” has undergone significant revisions. This art…

Definition of Risk

The definition of “risk” differed from that of the higher-order standard ISO 31000 (Risk management – Guidance and principles), which had long been recognized as a challenge. ISO 31000 defines risk as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives,” but ISO 14971, given its focus on the limited domain of medical devices, explicitly excludes “business risk” from its scope of application.

This explicit exclusion clarifies the rationale for the difference from ISO 31000’s definition. Risk management for medical devices is now positioned as a discipline that should focus on patient safety and product efficacy.

Definitions of Terms

In the 2019 version, the definitions of terms have been comprehensively updated, and three important new terms have been added:

“Benefit,” “Reasonably foreseeable misuse,” and “State of the art”

Addition of Benefit

In benefit/risk analysis, the 2007 version included a definition of “risk” but lacked a definition of “benefit.” It has become increasingly recognized that risk assessment for medical devices must consider not only risks but also the clinical and patient-side benefits that the medical device provides, balanced against those risks. Therefore, a formal definition of “benefit” has been added for the first time.

Reasonably Foreseeable Misuse

“Reasonably foreseeable misuse” is defined in alignment with ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014. This addition is extremely significant. Traditionally, only risks arising from use according to instructions were considered. However, in the 2019 version, reasonably foreseeable misuse by users or patients is now explicitly incorporated as a manufacturer responsibility.

For example, the potential for an oral medication dispenser to be misused as a syringe, or the possibility that a patient who is not a healthcare professional might use a device in an incorrect manner, falls within the scope of reasonably foreseeable misuse and must be evaluated. This change has broadened the scope of the manufacturer’s risk assessment responsibilities.

State of the Art

“State of the art” is a term frequently used by the FDA, and it is a critical concept recognized across medical device regulators worldwide. In simple terms, it refers to “the highest level of technology and knowledge currently available,” essentially a real-world benchmark.

The concept of state of the art encompasses multiple dimensions. Beyond the clinical evaluation conducted during device development (or performance evaluation for in vitro diagnostic (IVD) devices) and clinical trials, market feedback obtained after launch, adverse event reports, and clinical experience must be given significant weight. Once a medical device enters the market, it is used by a larger and more diverse user population across a wider range of use scenarios. This real-world experience provides critical information sources for risk signals that cannot be captured during the limited clinical trials conducted in the development phase.

Furthermore, “state of the art” includes the most current regulatory requirements and international standards. Given that medical device technology advances rapidly each year, it is imperative that design and development follow the latest international standards (such as IEC 60601-1: General requirements for safety and essential performance of medical electrical equipment, or IEC 62304: Medical device software lifecycle processes). Design modifications must be implemented as necessary to maintain compliance with evolving standards.

Additionally, the concept of state of the art encompasses the ongoing collection and review of data and literature concerning medical devices, similar medical devices, and competing products in the marketplace. This is not merely a development phase activity but is positioned as a continuing post-market activity.

Benefit/Risk Analysis

The 2007 version employed the term “risk/benefit analysis,” whereas the 2019 version changed this to “benefit/risk analysis.” This is not merely a terminological reversal but rather an intentional change that emphasizes the importance of benefit evaluation. It suggests a shift in the order of priority in evaluating medical device value: benefits that patients and clinicians may receive should be considered first, and risks should be assessed on that basis.

In particular, this analysis plays a critical role in decisions regarding the approval and market authorization of medical devices. While minimizing risk, the fundamental philosophy of medical device development is to deliver maximum benefit to patients.

ISO/TR 24971

As mentioned previously, most of the annexes in ISO 14971:2007 were relocated to ISO/TR 24971 and underwent substantial revision in the 2019 version. ISO/TR 24971 is positioned as a Technical Report and provides essential implementation guidance for ISO 14971.

When the 2019 version was released, ISO/TR 24971 was still in draft form, but subsequently, more detailed implementation guidance was added. To effectively implement risk management, continued updates and reference to this guidance document are strongly recommended. Rather than interpreting ISO 14971 literally alone, utilizing the implementation insights presented in TR 24971 enables organizations to construct more practical and effective risk management systems.

Personnel Competence

The change from “3.3 Personnel Qualification” to “4.3 Personnel Competence” reflects far more than a simple terminology change; it represents a significant shift in the management approach.

In ISO 9001:2015, “competence” is clearly defined as “the ability to apply knowledge and skills to achieve intended results.” This definition challenges the value of merely attending specific training courses or passing examinations.

Simply attending a training course does not qualify someone as a risk management professional. To understand this principle, the example of automobile driving is instructive. In a driver training school, classroom instruction provides “knowledge.” However, “knowledge” alone does not ensure safe driving. Subsequently, trainees must gain “training” through in-vehicle instruction and road driving practice. However, even after completing training and obtaining a driving license, safe and appropriate driving is not always guaranteed. Only through actual road experience under diverse conditions—various traffic situations, different weather conditions, night driving, and numerous other scenarios—does true driving competence become established.

The same logic applies to risk management personnel. Risk management personnel must be recognized as individuals with knowledge and skills only after they have undergone education (acquisition of theoretical knowledge), training (development of skills), and experience (application of practical knowledge and development of judgment capability). Organizations bear the responsibility not merely of recording personnel participation but of confirming personnel suitability through ongoing competence development and evaluation.

Related Articles

- ISO 14971:2019 Revisions – Part 2: Management Responsibility, Risk Analysis, and Risk Management File

- The Birth of 21 CFR Part 11: A Historical Perspective

- The Four Unsolvable Challenges of Part 11

- Understanding the “Typewriter Excuse” in FDA 21 CFR Part 11 Compliance

- The Evolution of Electronic Records Regulations: From FDA Part 11’s Tumultuous Past to Today’s Global Harmonization

- Correct Understanding of Electronic Signatures under 21 CFR Part 11

Comment