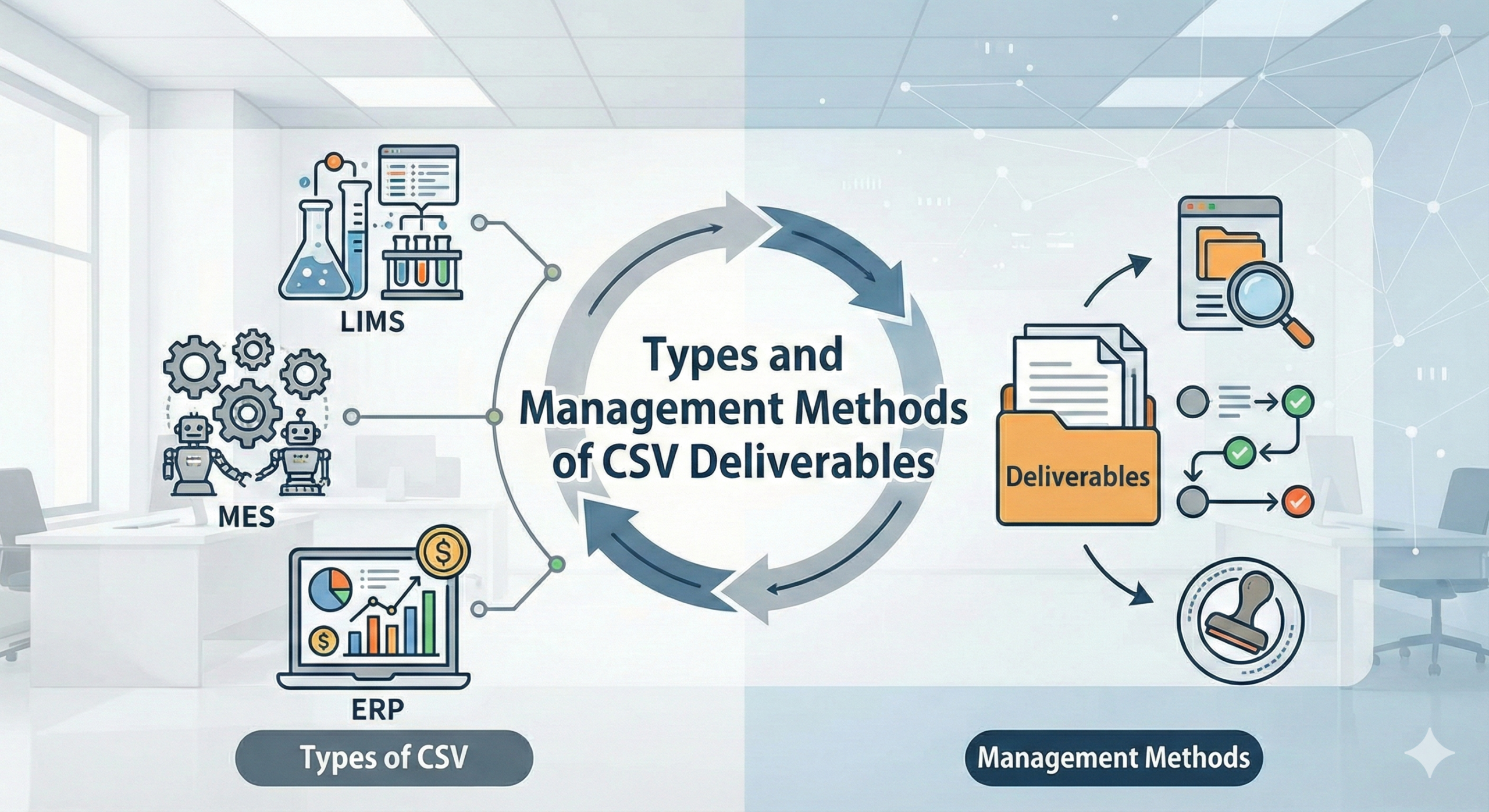

Types and Management Methods of CSV Deliverables

Types of CSV Deliverables

Documents created during the implementation of CSV (Computerized System Validation) are referred to as deliverables. According to GAMP 5, first published in 2008 (with a Second Edition released in 2022), there are approximately 60 types of deliverables categorized in the validation lifecycle.

💡 CSV成果物の種類と管理方法を正しく理解することは、コンピュータ化システムバリデーションの成功に不可欠です。

CSV deliverables can be broadly classified into several categories: plans, specifications, reports, scripts, and logs. Each category serves a distinct purpose in the validation lifecycle and must be managed according to its specific characteristics.

Plans

Plans clearly define who will do what and when. Specifically, they identify the CSV implementation organization, roles and responsibilities, and establish the project schedule. A critical principle is that technical details should not be included in plans. Technical matters must be documented in specifications.

In many projects, progress does not proceed according to the original plan. The primary reason for this is often that the initial plan itself was inappropriate. Schedules must be both feasible and reasonable. Unrealistic schedules lead to rushed work, inadequate testing, and ultimately compromise the quality of the validation effort.

Reports

Reports must not be mere copies of plans. It is virtually impossible for all activities to be executed exactly as planned. The essential purpose of reports is to document changes made to the plan and any deviations that occurred during execution.

Deviations are particularly important from a quality assurance perspective and must include documented justification. Without proper justification, deviations may indicate quality issues that could affect patient safety or data integrity. Reports should provide a complete and transparent record of what actually occurred during the validation process, including how issues were identified, assessed, and resolved.

Specifications

Specifications are technical documents that define system requirements and design. These include User Requirements Specifications (URS), Functional Specifications (FS), Design Specifications (DS), and Detailed Specifications (such as screen specifications, report specifications, database specifications, and program specifications). Each specification type serves a specific purpose in the validation hierarchy and must be traceable to higher-level requirements.

The specifications form the foundation for qualification and testing activities. They must be clear, complete, and unambiguous to ensure that the system can be properly validated and that testing can verify all critical requirements.

Scripts and Logs

Test scripts define the step-by-step procedures for executing tests, while test logs record the results of test execution. These documents provide objective evidence that the system has been properly tested and meets its specifications. Both successful tests and failed tests (including their investigation and resolution) must be documented.

Key Considerations for Creating Deliverables

Version Management of Specifications

Specifications must be created and maintained as one document per system, with version control applied to the entire document rather than creating separate documents for each project phase. For example, if an Electronic Document Management System (EDMS) implementation project was executed in 2010, followed by a functional enhancement project in 2013, and a partial modification and addition project in 2015, the following approach is incorrect:

Many organizations mistakenly create a User Requirements Specification in the 2010 project, then create an additional User Requirements Specification for the 2013 additions, and another for the 2015 changes and additions. This approach of creating only differential User Requirements Specifications for each project makes it impossible to get a complete view of the current user requirements for the system at a glance, and therefore it becomes unclear whether the system is properly validated.

The correct approach is to create Version 1.0 of the User Requirements Specification in 2010, revise it to create Version 2.0 in 2013, and further revise it to create Version 3.0 in 2015. This ensures that the current state of the system is always documented in a single, comprehensive specification document.

The same principle applies to Functional Specifications and Design Specifications. Differential specifications must not be created. It is essential that the current functionality of the system can be understood at a glance from the latest version of the specification.

This version control approach is critical for several reasons:

- Regulatory Compliance: Inspectors need to see the complete current state of the system, not a collection of change documents

- Maintenance Efficiency: Anyone maintaining the system needs access to complete, current documentation

- Change Control: All changes must be traceable through the version history

- Validation Status: The current validated state must be clearly documented

Version Management of Management Documents

In contrast, management documents such as plans and reports must be created separately for each project. The Validation Plan and Validation Report from the 2010 project are self-contained within that project. For the 2013 project, the Validation Plan and Validation Report must be created as new Version 1.0 documents specific to that project alone.

Past Validation Plans and Validation Reports must never be revised or reused. Each project represents a distinct validation effort with its own scope, schedule, and acceptance criteria. Mixing validation efforts across projects would compromise the integrity of the validation documentation and make it difficult to demonstrate compliance during regulatory inspections.

This separation maintains clear boundaries between validation projects and ensures that each project’s validation activities are properly documented and justified independently.

Storage Methods for Deliverables

Storage of Plans, Reports, and Specifications

For plans, reports, and specifications, only the latest version must be kept in binders or electronic document management systems. Superseded versions should be archived according to the organization’s document retention procedures but should not be maintained in active use alongside current versions. This prevents confusion about which version represents the current validated state.

Storage of Test Scripts and Test Logs

In contrast, all versions of test scripts and test logs must be retained in binders or electronic archives. This is a critical requirement because keeping only the latest test logs would show only successful tests.

Regulatory inspectors do not primarily want to examine successful tests during reviews. Rather, they want to review tests that resulted in errors or failures to investigate how those issues were identified, investigated, and resolved. The complete testing history, including failed tests, retests, and investigations, demonstrates the rigor of the validation process and provides confidence in the final validated state.

This complete test documentation serves several purposes:

- Evidence of Thorough Testing: Shows that problems were identified and addressed

- Investigation Records: Documents the root cause analysis for failures

- Retest Evidence: Proves that corrections were effective

- Audit Trail: Provides a complete history of qualification activities

- Regulatory Defense: Demonstrates a scientifically sound validation approach

The retention of all test documentation is a fundamental requirement of GxP regulations and demonstrates that the validation was conducted with appropriate scientific rigor and transparency.

Contemporary Considerations

Risk-Based Approach

Modern CSV practices, as emphasized in GAMP 5 Second Edition and regulatory guidance, increasingly focus on risk-based approaches. The extent and rigor of deliverables should be proportionate to the risk the system poses to patient safety, product quality, and data integrity. Critical systems require more comprehensive documentation, while lower-risk systems may justify streamlined deliverables.

Electronic Records and Signatures

Organizations must ensure that electronic document management systems used to store CSV deliverables comply with applicable regulations such as 21 CFR Part 11 (FDA), Annex 11 (EU), and equivalent regulations in other jurisdictions. Electronic signatures on validation documents must meet regulatory requirements for authenticity, integrity, and non-repudiation.

Ongoing Verification and Continuous Process Verification

The validation lifecycle doesn’t end with initial validation. Modern regulatory expectations emphasize ongoing verification activities and periodic review to ensure systems remain in a validated state throughout their operational life. This requires appropriate procedures for change control, periodic review, and revalidation when necessary.

Related Articles

- Why Software Category Classification is Necessary

- The Purpose and Importance of Installation Qualification (IQ) in the Pharmaceutical Industry

- Understanding the True Purpose of Performance Qualification (PQ) in Computerized System Validation

- Purpose and Proper Development of Validation Reports

- Risk-Based Approach in FDA Regulations: A Modern Framework for Computer System Validation

📌 関連テンプレート: CSV関連キット

Comment