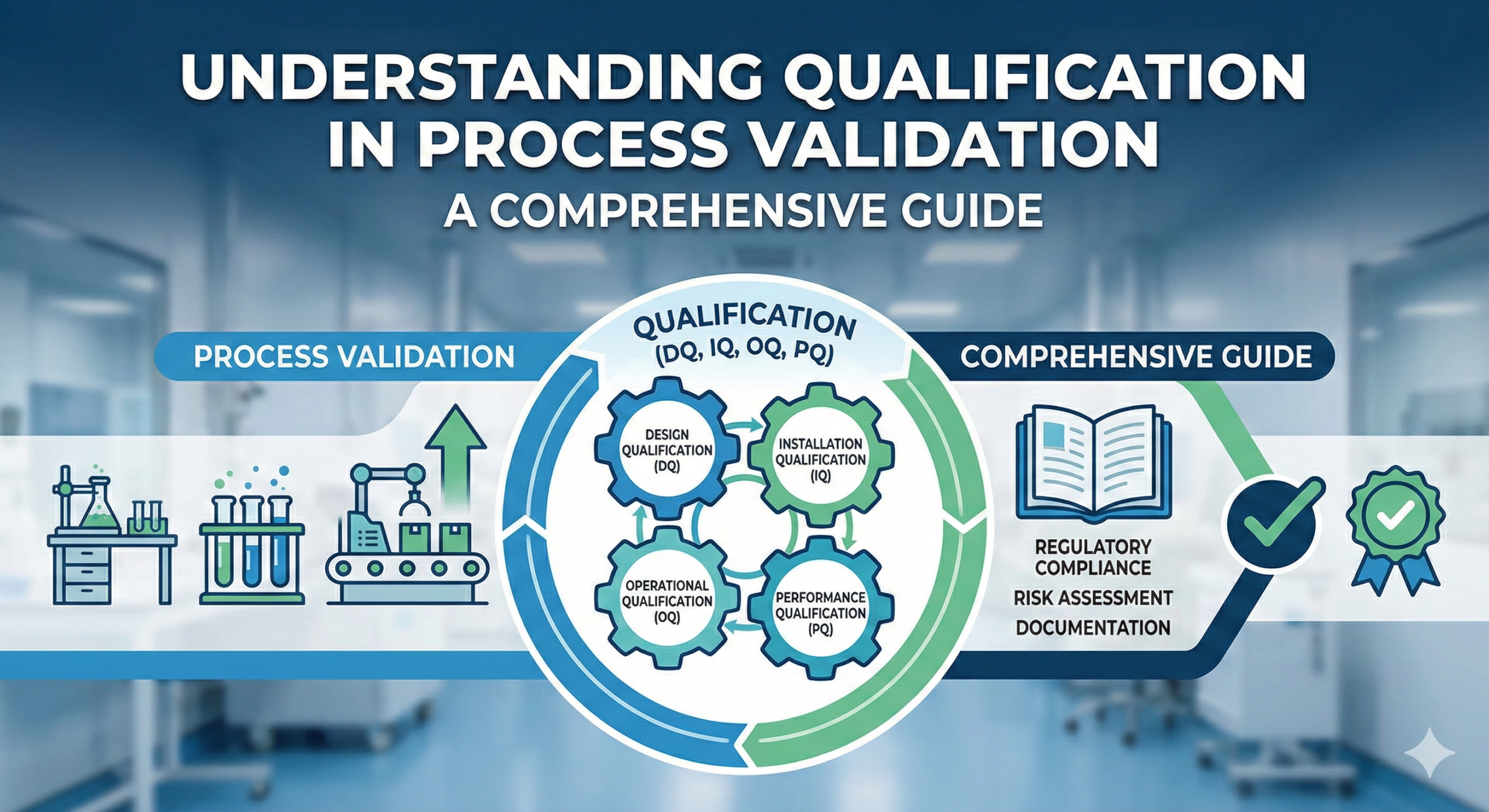

Understanding Qualification in Process Validation: A Comprehensive Guide

What is Qualification?

In process validation, qualification of facilities, utilities, and equipment must be conducted before initiating the validation process itself. Qualification, derived from the English term “Qualification,” comprises four distinct phases: Design Qualification (DQ), Installation Qualification (IQ), Operational Qualification (OQ), and Performance Qualification (PQ). While these qualification phases are also employed in Computerized System Validation (CSV), it is important to understand their proper application and recent regulatory developments regarding their use.

So what exactly does qualification entail? In healthcare industries such as pharmaceuticals and medical devices, it is essential to ensure that equipment specifications align with requirement specifications. Let us illustrate this concept with clear examples.

Imagine attempting to tighten a Phillips-head screw without a Phillips screwdriver. While it may be technically possible to use a flathead screwdriver, the flathead screwdriver is not “qualified” for a Phillips screw. Repeated use in this manner will damage the screw head and eventually break the screwdriver itself. Similarly, consider performing surgery with a kitchen knife instead of a surgical scalpel—the consequences would clearly be unacceptable and potentially catastrophic.

When the intended use does not match the specifications of equipment or tools, accidents and failures occur in pharmaceutical manufacturing and other regulated processes. This is precisely why we must “evaluate the qualification” of hardware before proceeding with process validation. In essence, qualification represents the validation of physical facilities, utilities, and equipment—the hardware components of manufacturing systems.

The terminology of IQ, OQ, and PQ fundamentally applies to hardware systems. Hardware consists of physical equipment, and in the case of automated systems, this hardware operates under software control.

Important Clarification: Qualification Terminology and Software Systems

A critical distinction must be made regarding the application of qualification terminology. While some organizations continue to use IQ, OQ, and PQ terminology for pure software applications (such as IT applications without dedicated hardware), this practice requires careful consideration in light of modern regulatory guidance.

The FDA’s General Principles of Software Validation (1997, updated 2025) explicitly acknowledged that “IQ/OQ/PQ terminology has served its purpose well and is one of many legitimate ways to organize software validation tasks at the user site, this terminology may not be well understood among many software professionals.” The guidance noted that this terminology originates from process validation contexts and may not align naturally with modern software development and validation practices.

More significantly, the FDA’s Computer Software Assurance (CSA) guidance, finalized in September 2025, represents a paradigm shift away from traditional qualification approaches for software systems. The CSA guidance emphasizes risk-based testing approaches (scripted testing and unscripted testing) rather than the traditional IQ/OQ/PQ framework. Industry experts now recognize that “IQs, OQs and PQs are very ineffective in a typical large-scale modern software development or configuration environment, where those kinds of deliverables are just not a natural or useful part of the lifecycle.”

For software-only systems, the appropriate approach is to implement software testing methodologies that include unit testing, integration testing, system testing, and user acceptance testing (UAT), aligned with the intended use and risk profile of the software. These testing approaches should be scaled based on the software’s complexity, novelty, and potential impact on product quality or patient safety.

However, for automated systems and equipment that combine both hardware and software (such as manufacturing equipment controlled by programmable logic controllers, laboratory instruments with software interfaces, or automated production lines), the IQ/OQ/PQ terminology remains appropriate and widely used in the pharmaceutical and medical device industries. In these cases, IQ verifies proper hardware installation, OQ tests the integrated hardware-software system’s operational parameters, and PQ confirms performance under actual production conditions.

Contemporary Approaches to Qualification

In recent years, the qualification landscape has evolved significantly. Modern manufacturing increasingly relies on commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) products and pre-validated equipment rather than custom-designed systems. Consequently, the importance and intensity of qualification activities have shifted compared to earlier eras when equipment was individually designed and manufactured for specific applications.

Current regulatory thinking and industry best practices now permit more streamlined qualification approaches:

Design Qualification (DQ): While DQ remains valuable for custom-designed systems, it may be abbreviated or incorporated into User Requirements Specifications (URS) for COTS equipment. The emphasis is on confirming that purchased equipment specifications match the intended manufacturing requirements.

Combined Installation and Operational Qualification (IOQ): Rather than conducting IQ and OQ as strictly sequential phases, these can now be combined into a single IOQ phase. This approach recognizes that for many modern equipment types, installation verification and operational testing can be efficiently performed together without compromising quality or compliance.

Performance Qualification (PQ): PQ remains critical as it demonstrates that equipment performs consistently under actual production conditions. However, modern approaches may leverage supplier-provided performance data and adopt risk-based protocols rather than exhaustive testing of every parameter.

Supplier Involvement: Qualification activities, particularly IOQ, may be delegated to qualified equipment suppliers or vendors. Many equipment manufacturers now provide Factory Acceptance Testing (FAT) and Site Acceptance Testing (SAT) as part of their standard offerings. However, it is essential to understand that ultimate responsibility for qualification remains with the user organization (the pharmaceutical or medical device manufacturer). The user must:

- Establish clear qualification requirements in purchase specifications

- Review and approve supplier qualification protocols

- Verify supplier qualification results

- Maintain appropriate oversight of supplier activities

- Retain qualification documentation as part of the manufacturing facility’s validation master file

This delegation strategy allows manufacturers to leverage supplier expertise while maintaining regulatory compliance and quality assurance. The approach aligns with the principle of utilizing available vendor evidence and avoiding unnecessary duplication of testing, as emphasized in modern regulatory guidance including FDA’s Computer Software Assurance principles.

Risk-Based Qualification in Modern Practice

Contemporary qualification should follow a risk-based approach that focuses resources on critical equipment and high-risk functions. Not all equipment requires the same level of qualification rigor. Equipment that directly contacts product, controls critical process parameters, or generates data for regulatory submissions requires more comprehensive qualification than ancillary or support equipment.

The qualification strategy should be documented in a Master Validation Plan or Validation Master File that establishes:

- Equipment categories based on risk and GMP impact

- Appropriate qualification approaches for each category

- Responsibilities for qualification execution and documentation

- Acceptance criteria aligned with process requirements

- Change control procedures for qualified equipment

Documentation and Compliance Considerations

Qualification documentation serves multiple purposes: it provides evidence of compliance, supports process understanding, facilitates troubleshooting, and enables effective change control. However, modern regulatory expectations emphasize meaningful documentation over voluminous paperwork. Qualification records should be sufficient to demonstrate that equipment is fit for its intended use without creating unnecessary documentation burden.

Electronic records, system logs, and digital documentation are increasingly preferred over paper-based systems, provided they meet requirements for data integrity, traceability, and security as outlined in 21 CFR Part 11 and related guidance.

Integration with Process Validation

It is important to recognize that qualification represents the foundation for process validation, not a substitute for it. Even fully qualified equipment must undergo process validation to demonstrate that the complete manufacturing process consistently produces products meeting predetermined specifications. The relationship can be understood hierarchically:

- Equipment qualification establishes that individual components are suitable for their intended use

- Process validation demonstrates that the integrated system of qualified equipment, materials, methods, and personnel consistently produces acceptable product

- Continued process verification ensures the validated state is maintained over time

In conclusion, qualification remains a fundamental element of pharmaceutical and medical device quality systems. While modern approaches emphasize risk-based strategies, supplier collaboration, and streamlined documentation, the core principle endures: equipment and systems must be demonstrated suitable for their intended use before implementation in GMP production. Organizations that understand both traditional qualification concepts and contemporary regulatory thinking are best positioned to implement efficient, compliant, and scientifically sound qualification programs.

Note: This article reflects current regulatory thinking as of January 2025, including the FDA’s Computer Software Assurance guidance (September 2025) and ISPE GAMP®5 principles. Organizations should consult applicable regulations (21 CFR Part 211, 21 CFR Part 820, EU GMP Annex 15, ICH Q7) and current guidance documents when developing qualification strategies.

Comment