Human Error Is Not a Root Cause

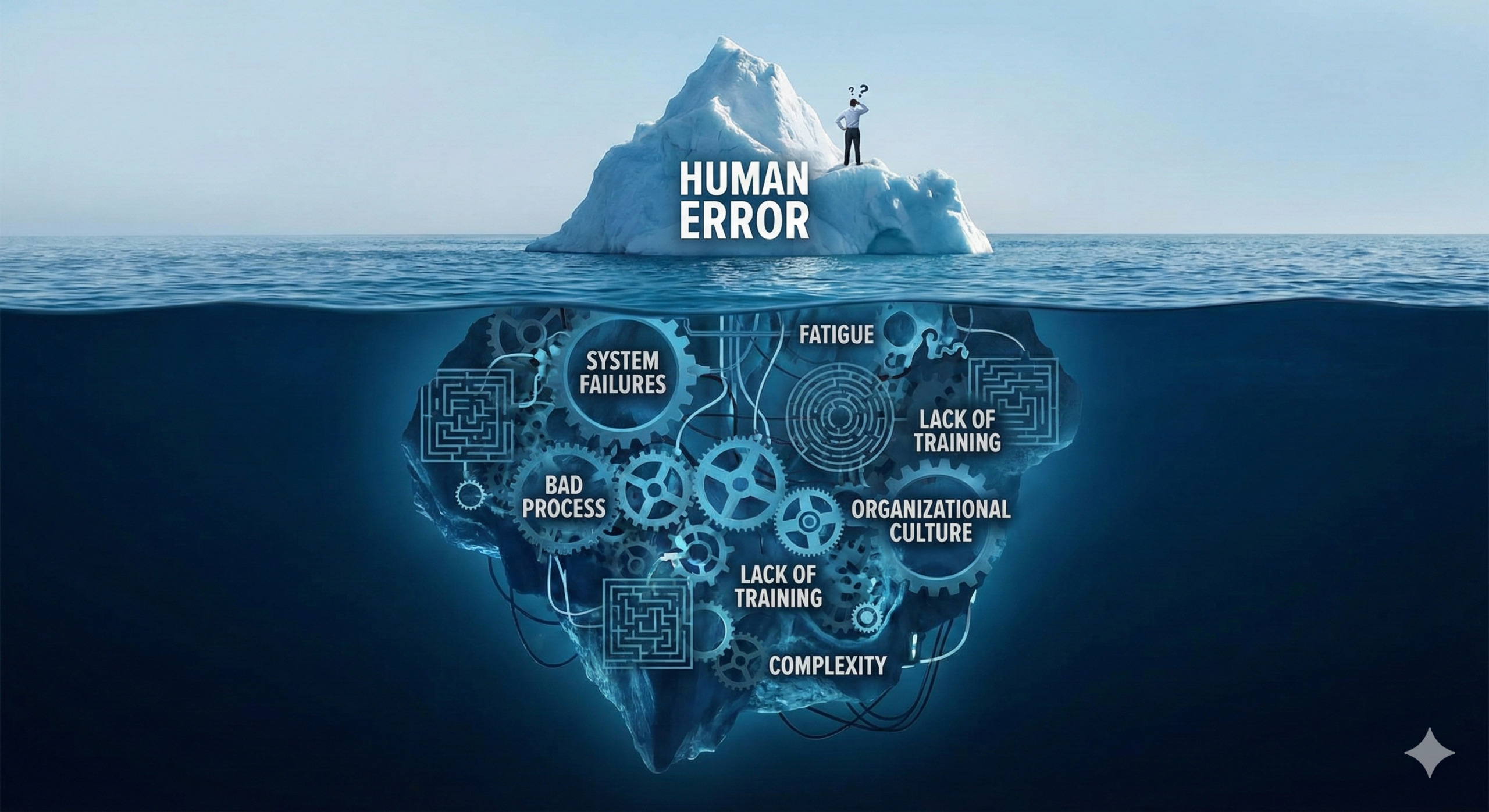

When deviations occur in manufacturing processes or quality testing, it is common to see human error identified as the root cause in Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) investigations. However, according to former FDA inspectors, the FDA has not accepted human error as a root cause for more than a decade. The true root cause must always lie within the quality system itself.

Understanding Why Human Error Alone Is Insufficient

Consider this scenario: an employee makes a mistake, and their supervisor reprimands them severely. That particular employee may never repeat the same mistake. However, when organizational changes occur and a new employee assumes responsibility for that process, the same mistake is likely to recur. This demonstrates that the issue is not the individual but rather the absence of systematic controls.

Therefore, organizations must embed mechanisms within their quality systems to either prevent similar failures or detect them when they occur. This is not merely a best practice—it is a fundamental requirement of modern pharmaceutical quality systems as outlined in ICH Q10 and medical device quality management systems per ISO 13485:2016.

The Problem with Individualized Corrective Actions

A critical principle in implementing corrective actions is recognizing that measures targeting only individuals or specific products are insufficient and create a high risk of recurrence. When corrective actions remain at the personal level without being integrated into the quality system, they fail to provide sustainable protection against future problems.

For example, addressing an issue in a company meeting and attempting horizontal deployment may temporarily raise awareness, but without systemic changes, the same problem will likely resurface over time. The solution requires creating mechanisms (systems) that ensure continuous monitoring and building knowledge databases that can be leveraged as organizational know-how.

The Five Whys: Pursuing Systemic Root Causes

The essential question is: “Why did this situation occur?” Organizations must diligently pursue this “why” to identify the true root cause. When conducting root cause analysis, the focus should be on identifying systemic defects, weaknesses, inadequacies, contradictions, or ambiguities within the quality system itself.

The core of corrective action (preventing recurrence) lies in addressing these systemic issues—system-level defects, weaknesses, inadequacies, contradictions, and ambiguities. If corrective actions rely on human factors such as discipline, attention, or awareness, problems will inevitably recur.

The Reality of Human Nature and Quality Systems

Human nature inherently tends toward complacency and inattention. Quality systems that depend on discipline and vigilance cannot sustain consistent quality indefinitely. Eventually, someone—possibly even the same individual—will reproduce similar problems. This is why regulatory authorities and international standards emphasize system-based approaches rather than person-based solutions.

Why “Training” Is Not a Corrective Action

One frequently encountered inadequate corrective action is “thorough training implementation.” While training is an essential component of quality management, stating that training has been “thoroughly implemented” does not constitute an effective corrective action. This is explicitly recognized in both FDA guidance and ISO 13485 requirements.

According to current regulatory expectations:

- Training alone does not address the systemic causes that allowed the error to occur in the first place

- Without changes to procedures, work instructions, equipment design, or process controls, the conditions that led to the error remain unchanged

- Effective corrective actions must modify the system to either prevent the error condition or detect it before it results in a nonconformity

Regulatory Perspective on Root Cause Analysis

FDA Requirements (21 CFR Part 820.100)

The FDA’s Quality System Regulation requires that failure investigations determine root cause “where possible.” The regulation emphasizes that:

- Root cause analysis must identify systemic issues

- Corrective actions must address underlying system deficiencies

- The effectiveness of corrective and preventive actions must be verified

- Human error as a root cause signals inadequate investigation depth

ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality System

ICH Q10, which complements Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) requirements, establishes that an effective pharmaceutical quality system must:

- Monitor process performance and product quality systematically

- Implement CAPA systems that identify and address systemic root causes

- Use quality risk management principles to identify areas for improvement

- Facilitate continual improvement through knowledge management

The guideline explicitly states that quality systems should “provide assurance of the continued capability of processes and controls to produce a product of desired quality and to identify areas for continual improvement.”

ISO 13485:2016 for Medical Devices

ISO 13485:2016 addresses corrective actions in Clause 8.5.2 and preventive actions in Clause 8.5.3. The standard requires:

- Elimination of the causes of nonconformities without delay

- Actions appropriate to the impact of the problems encountered

- Documentation of root cause analysis and corrective action effectiveness

- Verification that actions do not adversely affect regulatory compliance or device safety and performance

Best Practices for Identifying Systemic Root Causes

Effective root cause analysis in regulated industries should employ structured methodologies such as:

Fishbone (Ishikawa) Diagram

Systematically identifies potential causes across categories: Methods, Machines, Materials, Measurements, Environment, and People (the 6Ms). While “People” is a category, the analysis should focus on why the system allowed the person to make the error.

5 Whys Analysis

Repeatedly asking “why” (typically five times) to drill down from symptoms to underlying systemic causes. The goal is to move beyond “the operator forgot” to understand why the system design allowed forgetfulness to result in a quality problem.

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

Proactively identifies potential failure modes and their causes, which helps design systems that are inherently resistant to human error.

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) Tools

More sophisticated approaches like the TapRooT® System or Apollo Root Cause Analysis provide structured frameworks that guide investigators toward systemic findings.

Examples of Systemic Root Causes vs. Human Error

| Initial Finding (Insufficient) | Systemic Root Cause (Appropriate) |

| Operator forgot to record temperature | No automated alarm when recording was overdue; procedure did not require immediate recording at point of observation |

| Employee entered wrong data | Data entry field accepted out-of-range values; no verification step in process; similar fields not clearly differentiated |

| Worker skipped a process step | Work instruction unclear or ambiguous; process design allowed step to be easily missed; no built-in verification mechanism |

| Person used wrong material | Material containers inadequately labeled; storage location allowed wrong materials to be accessible; no barcode scanning or visual verification system |

| Analyst made calculation error | Manual calculation required instead of automated calculation; no independent check required by procedure; calculation worksheet not validated |

Building Error-Resistant Systems

Rather than expecting perfection from individuals, organizations should design quality systems that are inherently resistant to human error. This approach, often called “error-proofing” or “poka-yoke” (from Japanese manufacturing principles), includes:

Design Controls

- Automated monitoring and alarms

- Interlocks that prevent incorrect operations

- Software validation to prevent data entry errors

- Equipment design that makes errors impossible or immediately obvious

Procedural Controls

- Clear, unambiguous procedures with visual aids

- Built-in verification steps at critical points

- Redundancy for critical operations (e.g., independent double-checks)

- Standardized formats that reduce cognitive load

Environmental Controls

- Workspace design that reduces distractions

- Adequate lighting, ergonomics, and environmental conditions

- Clear demarcation and labeling of materials, equipment, and areas

- Workflow design that follows natural human tendencies

Training and Competency

While training alone is insufficient as corrective action, it remains essential when combined with systemic improvements:

- Initial qualification demonstrating competency

- Periodic requalification and assessment

- Training on updated procedures following corrective actions

- Documentation of training effectiveness

The Role of Human Factors Engineering

Modern quality systems increasingly incorporate human factors engineering (HFE) principles, which recognize that:

- Humans have predictable limitations and capabilities

- Systems should be designed to accommodate human characteristics

- Errors often result from poor human-system interfaces

- Designing systems to prevent or catch errors is more effective than relying on vigilance

The FDA and other regulatory agencies now explicitly consider human factors in their evaluation of quality systems, particularly for critical processes.

Management Review and Continuous Improvement

ICH Q10 and ISO 13485 both require management review of quality system performance, including:

- Effectiveness of corrective and preventive actions

- Trends in nonconformities and quality metrics

- Opportunities for improvement identified through data analysis

- Resource allocation for quality system enhancements

This management oversight ensures that CAPA systems drive genuine systemic improvement rather than superficial responses to individual incidents.

Conclusion: System Accountability, Not Personal Blame

The principle that human error is not a root cause reflects a fundamental shift in quality management philosophy from personal accountability to system accountability. This does not mean that individuals bear no responsibility for following procedures. Rather, it recognizes that when errors occur, especially repeatedly, the system has failed to adequately prevent or detect them.

Effective quality systems are characterized by:

- Systematic identification and analysis of quality problems

- Root cause analysis that identifies systemic issues

- Corrective actions that modify systems, not just retrain individuals

- Verification of corrective action effectiveness through objective evidence

- Continuous improvement based on accumulated knowledge and experience

By focusing on systemic improvements rather than individual mistakes, organizations create quality systems that are sustainable, scalable, and genuinely effective at preventing recurrence. This approach not only satisfies regulatory expectations but also leads to superior product quality and enhanced patient safety—the ultimate goal of all pharmaceutical and medical device quality systems.

When an organization truly embraces this principle, quality becomes embedded in the system itself rather than depending on the vigilance of any individual. This is the essence of modern quality management and the foundation of regulatory compliance in the 21st century.

Comment