…

Introduction

One of the questions frequently posed to regulatory affairs professionals is: “What types of companies are subject to routine FDA inspections?” Understanding how the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) selects facilities for inspection is crucial for manufacturers, quality assurance personnel, and compliance professionals working in the pharmaceutical and medical device industries. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the FDA’s risk-based approach to selecting facilities for routine surveillance inspections, examines the evolution of inspection policy from fixed-interval requirements to risk-based prioritization, and discusses current challenges and recent regulatory developments.

The Site Selection Model: A Risk-Based Approach

The FDA employs a Site Selection Model (SSM) to calculate a risk score for all manufacturing sites in its catalog using evidence-based risk factors. This mathematical model enables the agency to prioritize facilities with the greatest potential for public health risk should they fail to comply with established manufacturing quality standards. The SSM was originally developed and implemented in fiscal year (FY) 2005 as part of the FDA’s initiative “Pharmaceutical Quality for the 21st Century — A Risk-Based Approach.” This represented a fundamental shift from the previous approach, which was based primarily on a fixed biennial inspection frequency for domestic sites.

The Office of Surveillance (OS) within the Office of Pharmaceutical Quality (OPQ) is responsible for producing the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research’s (CDER’s) Site Surveillance Inspection List (SSIL), which prioritizes sites for surveillance inspections. This list is developed by inputting sites from CDER’s Catalog of Manufacturing Sites into the SSM. The Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) is then responsible for planning and conducting inspections based on this prioritized list.

Risk Factors Used in the Site Selection Model

The SSM incorporates multiple risk factors that relate to drug product quality and the sites that manufacture them. According to the FDA’s Manual of Policies and Procedures (MAPP) 5014.1, originally published in September 2018 and revised in July 2023, the risk factors are based on either empirical evidence collected by FDA, the judgment of subject matter experts, or a combination of both. The agency has committed to achieving parity in inspection frequency, meaning equal frequency for sites with equivalent risk regardless of geography (foreign versus domestic) or product type (whether originator, generic, or over-the-counter monograph).

1. Inherent Product Risk

Different types of products carry different levels of risk based on characteristics such as dosage form, route of administration, and whether the product is intended to be sterile. The SSM considers multiple aspects of inherent product risk including:

- Dosage form characteristics

- Route of administration (e.g., injectable, oral, topical)

- Sterility requirements

- Active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) load (concentration of API in dosage form or unit dose)

- Biologic drug substance or drug product

- Therapeutic class

- Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs

- Emergency use drugs

For example, a manufacturing facility that produces sterile injectable drug products will have a higher inherent product risk compared to a facility that manufactures oral capsules or tablets. This reflects the greater potential for patient harm if quality issues arise with products requiring sterility or those administered via higher-risk routes.

2. Facility Type (Site Type)

Risk levels vary depending on the operations that a facility performs. The SSM differentiates between various types of manufacturing operations, including:

- Drug product manufacturers

- Active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturers

- Packagers only

- Control laboratories only

- In-process material manufacturers

Facilities that manufacture drug products or active pharmaceutical ingredients are considered higher risk than facilities that only package finished drug products, as the former operations involve more critical manufacturing steps where quality defects can originate.

3. Patient Exposure

Patient exposure is a critical risk factor that reflects the potential impact on public health. The more products a facility manufactures, and the larger the volume of distribution, the more likely patients are to encounter products manufactured at that facility. This risk factor considers both:

- The number of different products manufactured at the facility

- The volume of drug products manufactured and distributed

A facility that manufactures many products or produces high-volume medications that treat large patient populations will have a higher patient exposure factor than a facility that manufactures only a few low-volume specialty products. This ensures that facilities whose operations affect more patients receive appropriate regulatory attention.

4. Compliance History

The compliance history of an establishment is a fundamental indicator of risk. Facilities that have failed to meet quality standards established during previous inspections are considered higher risk than those that have consistently met standards in the past. The SSM evaluates:

- Previous inspection outcomes (No Action Indicated, Voluntary Action Indicated, or Official Action Indicated classifications)

- Warning letters issued to the facility

- Consent decrees or other enforcement actions

- The nature and severity of previous violations

The FDA’s approach recognizes that past performance is often predictive of future compliance. Facilities with a history of significant violations require more frequent oversight to ensure corrective actions have been effectively implemented and sustained.

5. Time Since Last Inspection

As the time since a facility was last inspected increases, so does the uncertainty regarding whether it continues to meet established quality standards. The SSM incorporates time since last surveillance inspection as a risk factor, with the understanding that:

- Sites that have never been inspected require evaluation to establish baseline compliance

- Sites with extended periods since last inspection may have implemented changes to their operations, quality systems, or product portfolio that warrant verification

- The longer the interval since inspection, the greater the need for reassessment

Notably, newly registered sites should expect to be inspected within 30 days after registering with FDA, ensuring prompt verification of compliance for new market entrants.

6. Hazard Signals

Events that suggest potential quality problems result in higher risk scores. The SSM monitors various hazard signals including:

- Product recalls, particularly those classified as Class I (most serious) or Class II

- Field Alert Reports (FARs)

- Biological Product Deviation Reports (BPDRs)

- MedWatch reports (adverse drug event reports from consumers, physicians, and pharmacists that are potentially related to manufacturing quality)

- Customer complaints suggesting manufacturing issues

- Drug shortage notifications

These hazard signals serve as early warning indicators that a facility may be experiencing quality system problems requiring investigation. Facilities with frequent or serious hazard signals are prioritized for inspection.

7. Foreign Regulatory Authority Inspectional History

The SSM also considers inspection results from foreign regulatory authorities that FDA has deemed capable under section 809 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act. Under Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) between FDA and certain foreign regulatory authorities, FDA can rely upon information from drug inspections conducted by these authorities. This factor recognizes that:

- Inspections by recognized foreign regulators provide valuable information about facility compliance

- Collaborative international oversight enhances overall drug safety

- Efficient use of resources can be achieved through reliance on trusted foreign regulatory partners

As of 2025, FDA has MRAs with regulatory authorities in the European Union, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and several other countries.

8. Compliance History of Establishments in the Country or Region (Added 2023)

In the July 2023 revision of MAPP 5014.1, FDA added a new risk factor relating to the compliance history of establishments in the country or region where the facility is located. This addition reflects recognition that:

- Regional compliance patterns can indicate systemic issues

- Countries or regions with higher rates of serious violations may require enhanced scrutiny

- Contextual factors related to regulatory infrastructure and manufacturing culture can affect individual facility risk

This new factor has generated some industry discussion, as it potentially affects facilities with good individual compliance histories that happen to be located in regions with relatively poorer overall compliance rates. However, the facility-specific compliance history remains one of the most heavily weighted factors in the overall risk calculation.

Evolution of FDA Inspection Requirements: From Fixed Intervals to Risk-Based Scheduling

Original Statutory Requirements

Prior to 2012, section 510(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act required that drug and device establishments registered with FDA be inspected at least once in the two-year period beginning with the date of registration, and at least once in every successive two-year period thereafter. This biennial inspection requirement applied to domestic establishments and was codified in FDA regulations for biological products at 21 CFR 600.21 since 1983.

The Challenge of Maintaining Fixed-Interval Inspections

While the biennial inspection mandate represented Congress’s intent to ensure regular oversight of drug manufacturing, practical realities made this requirement increasingly difficult to maintain. Several factors contributed to this challenge:

- Limited Inspection Resources: FDA faced constraints in increasing the number of qualified investigators proportionally to the growth in regulated facilities. The agency’s inspection workforce could not expand rapidly enough to keep pace with industry growth.

- Globalization of the Drug Supply Chain: By the 2000s, supply chains had become increasingly global. Drug manufacturing had expanded significantly to Japan, Europe, China, India, and numerous other countries. FDA estimates that as of 2024, approximately 74 percent of establishments manufacturing active pharmaceutical ingredients and 54 percent of establishments manufacturing finished drug products for the U.S. market are located overseas.

- Practical Impossibility: Conducting biennial inspections of all registered domestic facilities was already challenging. Adding the requirement to inspect foreign facilities on the same schedule made the biennial mandate effectively impossible to fulfill.

The 2005 Risk-Based Initiative

Recognizing these challenges, FDA implemented a risk-based approach to prioritizing human drug manufacturing sites for routine CGMP surveillance inspection in FY2005. This was one of many outcomes from the initiative “Pharmaceutical Quality for the 21st Century — A Risk-Based Approach,” which represented a fundamental rethinking of pharmaceutical quality regulation. The FY2005 SSM replaced the previous approach based on fixed biennial inspection frequency for domestic sites.

However, it is important to note that while FDA began using the SSM in 2005 as a matter of policy, the statutory requirement for biennial inspections remained in place at that time.

The Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) of 2012

The legal framework for risk-based inspections was formally established with the enactment of FDASIA on July 9, 2012. Section 705 of FDASIA amended section 510(h) of the FD&C Act, making several critical changes:

- Eliminated the Fixed Biennial Requirement: FDASIA replaced the fixed minimum inspection interval for domestic drug establishments with the requirement that FDA inspect domestic and foreign drug establishments “in accordance with a risk-based schedule.”

- Codified Risk-Based Factors: The amendment specified that the risk-based schedule should consider establishments’ “known safety risks” and enumerated specific risk factors to be considered.

- Achieved Domestic-Foreign Parity: FDASIA mandated that the risk-based approach apply equally to domestic and foreign establishments, promoting parity in inspection frequency for sites with equivalent risk regardless of geographic location.

- Provided Statutory Basis for SSM: The legislation essentially codified the SSM approach that FDA had been using since 2005, while providing clear statutory authority for risk-based scheduling.

The statutory change largely adopted the SSM criteria in use since 2005; however, it allowed FDA to place less emphasis on a set frequency of inspection and more emphasis on the actual risk profile of each facility.

Subsequent Legislative Developments

The FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 (FDARA), signed into law on August 18, 2017, further amended section 510(h)(2) of the FD&C Act such that the biennial inspection schedule for device establishments was also replaced with a risk-based schedule, extending the risk-based approach to medical devices.

More recently, the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022 (FDORA), enacted as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 on December 29, 2022, expanded FDA’s inspection authorities in several important ways:

- Alternative Inspection Tools: Section 3613(b) of FDORA expanded FDA’s authority to use records and information in lieu of or in advance of inspections, providing flexibility in surveillance approaches.

- Regional Compliance Consideration: Section 3613(a) directed FDA to consider the compliance history of establishments in a particular country or region when determining the risk-based inspection schedule for facilities located there—the provision that led to the addition of this risk factor in MAPP 5014.1 Rev. 1.

- Drug Shortage Coordination: FDORA reestablished and made permanent coordination requirements before FDA takes enforcement actions that could reasonably lead to drug shortages.

The Shift to Foreign Inspections Since 2015

Milestone Achievement in FY2015

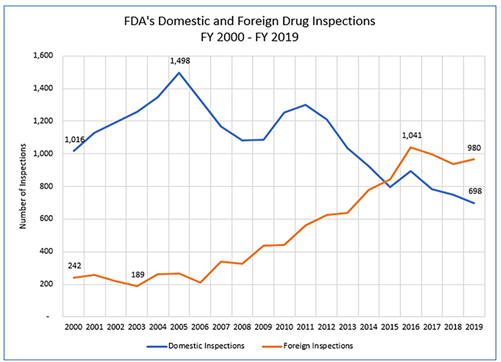

Fiscal year 2015 marked a significant milestone in FDA’s inspection program: for the first time, the total number of foreign drug manufacturing establishment inspections conducted by FDA exceeded the number of domestic inspections. This shift reflected the reality of global pharmaceutical manufacturing and FDA’s commitment to risk-based resource allocation.

Strategic Rationale for Increased Foreign Inspections

Several factors drove this strategic shift toward increased foreign inspection activity:

- Global Supply Chain Reality: With more than 60 percent of establishments manufacturing drugs for the U.S. market located overseas, foreign facilities represent a significant portion of the risk landscape.

- Concentration in Key Markets: As of 2019, India and China together accounted for approximately 40 percent of all foreign drug manufacturing establishments shipping drugs to the United States. These countries are major sources of both active pharmaceutical ingredients and finished drug products.

- Risk-Based Resource Allocation: The SSM’s risk-based approach naturally directed more resources to foreign facilities, as the model assessed risk without regard to geography. Many foreign facilities, particularly those manufacturing APIs or sterile injectables for the U.S. market, scored high on multiple risk factors.

- Previous Gaps in Oversight: GAO reports from 2008 and 2010 identified that FDA had never inspected many establishments manufacturing drugs for the U.S. market. The shift to increased foreign inspections addressed these gaps.

Building Foreign Inspection Capacity

FDA achieved this level of foreign inspection coverage by developing a mixed investigator workforce consisting of:

- U.S.-Based Investigators: Domestic investigators who perform both domestic and foreign inspections, traveling overseas as needed.

- Dedicated Foreign Cadre: A specialized group of U.S.-based drug investigators who conduct foreign inspections exclusively, developing expertise in international travel, cultural considerations, and coordination with foreign entities.

- Foreign Office-Based Investigators: Investigators stationed in FDA foreign offices located in strategic regions. FDA has established foreign offices in:

- China (Beijing)

- India (New Delhi)

- Europe (Brussels, Belgium and London, United Kingdom)

- Latin America (posts in Santiago, Chile; San Jose, Costa Rica; and Mexico City, Mexico)

Current Inspection Statistics and Trends

From FY2012 through FY2016, the number of foreign drug manufacturing establishment inspections increased consistently. However, from FY2016 through FY2018, both foreign and domestic inspections decreased—by approximately 10 percent and 13 percent respectively—primarily due to staffing vacancies among investigators.

In FY2019, FDA began to increase the number of foreign inspections again after these decreases. However, the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically disrupted inspection activities. Beginning in March 2020, FDA largely paused both foreign and domestic routine surveillance facility inspections, conducting only those deemed mission critical. In FY2020, FDA conducted only three foreign inspections following the pandemic pause—a stark reduction from recent years.

Current Challenges and Recent Developments

The COVID-19 Inspection Backlog

The COVID-19 pandemic created significant challenges for FDA’s inspection program. Most inspections were suspended from March 2020 through 2021, with regular international visits resuming only in 2022. As of May 2024, approximately 2,000 pharmaceutical manufacturing establishments had not been inspected by FDA staff since before the pandemic.

This backlog includes over 340 manufacturing plants in India and China, major sources of drug ingredients for the U.S. market. According to FDA guidelines, factories that have not been inspected for five or more years are considered a significant risk and are prioritized for mandatory inspection. The backlog represents a substantial challenge to maintaining adequate oversight of the drug supply chain.

Persistent Staffing Challenges

FDA continues to face significant challenges in recruiting and retaining a sufficient inspection workforce. As of June 2024, there were 225 vacancies in FDA’s inspection workforce—nearly four times the pre-COVID number. Factors contributing to this shortfall include:

- Extensive Travel Requirements: Foreign inspection work requires investigators to work independently in foreign establishments under constrained timeframes, with travel demands of up to 50 percent of their time.

- Compensation Disparities: Starting salaries for FDA investigators are lower compared to industry roles, and increased competition from the private sector has intensified recruitment challenges. Former FDA investigators can often earn more than double their FDA salary in private sector positions.

- Persistent Vacancies in Foreign Offices: As of November 2021, eight of 20 positions were vacant in FDA’s cadre of drug investigators that conduct only foreign inspections, and five of 15 drug investigator positions were vacant in foreign offices located in China and India.

- Recent Workforce Reductions: A reduction in force at FDA in 2024 eliminated a number of positions, further straining inspection capacity at a time when the agency was already struggling with vacancies.

Unique Challenges in Foreign Inspections

FDA has identified persistent challenges specific to foreign inspections that raise questions about the equivalence of foreign to domestic inspections:

- Preannouncement Practices: While domestic inspections are almost always unannounced, FDA’s standard practice has been to preannounce foreign inspections up to 12 weeks in advance. This advance notice may provide manufacturers with opportunities to address problems before inspectors arrive. In FY2023, nearly 90 percent of FDA’s foreign inspections were preannounced. Investigators from FDA’s China and India offices do conduct some unannounced inspections, but they are involved in only a small percentage of inspections in these countries (27 percent in China and 10 percent in India in earlier reporting periods).

- Translation Challenges: FDA continues to rely on translators provided by the foreign establishments being inspected, which investigators have noted can raise questions about the accuracy of information FDA investigators collect. Language barriers can create challenges during foreign inspections and potentially compromise the independence of the inspection process.

- Logistical Complexities: Foreign inspections face unique logistical challenges including:

- Extended travel time and costs

- Coordination across time zones

- Different regulatory and business cultures

- Limited ability to follow up quickly if additional information is needed

Despite these challenges, it is noteworthy that FDA investigators have continued to uncover serious deficiencies abroad—at more than twice the rate of domestic inspections—including documented instances of document destruction during inspections.

Recent Policy Developments and Strategic Initiatives

Several recent developments signal FDA’s ongoing efforts to address these challenges and enhance its foreign inspection program:

Executive Order (May 2025)

On May 5, 2025, President Donald J. Trump signed an executive order directing FDA to:

- Increase both user fees and the number of inspections of foreign manufacturing plants

- Expand the use of unannounced inspections at foreign facilities producing food, essential medicines, and other medical products for the U.S. market

- Strengthen enforcement of API source reporting requirements for foreign drug producers

This executive order is part of a broader initiative to encourage domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing and addresses what has been characterized as a “double standard” between domestic and foreign inspections.

Unannounced Foreign Inspection Pilot

FDA announced on May 6, 2025, plans to expand unannounced inspections at foreign manufacturing facilities. This initiative aims to:

- Achieve greater parity between foreign and domestic inspection practices

- Expose non-compliant operations more effectively

- Determine the feasibility and effectiveness of conducting unannounced foreign inspections on a broader scale

GAO has recommended that FDA incorporate leading practices for designing well-developed and documented pilot programs, including developing a methodology that details the information necessary to evaluate the pilot’s success.

Independent Translation Services Pilot

FDA is planning a pilot program focused on using independent translation services rather than relying on establishment-provided translators. This pilot aims to:

- Enhance the independence and accuracy of information collection during foreign inspections

- Address long-standing concerns about potential conflicts of interest

- Determine the practical feasibility and cost-effectiveness of independent translation

Both pilot programs were delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and as of late 2024, FDA had not yet finalized their designs.

Enhanced Foreign Inspection Policy (February 2024)

In February 2024, FDA announced evaluation of its inspection-related policies and practices with the goal of enhancing the integrity and effectiveness of its foreign inspection program. Proposed changes included:

- Formal guidance empowering investigators to refuse travel accommodations (lodging, transportation) offered by inspected entities to preserve independence

- Reaffirmation of FDA’s authority to take enforcement action against facilities that delay, deny, limit, or refuse inspection

- Enhanced protocols for documentation and communication during foreign inspections

Alternative Inspection Tools

During the COVID-19 pandemic, FDA developed and utilized alternative inspection tools to maintain some oversight of drug manufacturing quality while on-site inspections were paused. These tools have continued to supplement traditional inspections:

Reliance on Foreign Regulatory Authority Inspections

FDA has determined that inspections conducted by certain European regulators under MRAs are equivalent to and can be substituted for an FDA inspection. This reliance mechanism allows FDA to:

- Leverage inspections conducted by trusted foreign regulatory partners

- Allocate inspection resources more efficiently

- Maintain oversight continuity when FDA inspections are not feasible

However, FDA has emphasized that this reliance applies only to regulatory authorities that it has specifically deemed capable under section 809 of the FD&C Act.

Records and Information Requests

Under section 704(a)(4) of the FD&C Act, originally limited to drug establishments and expanded by FDORA to device establishments and bioresearch monitoring sites, FDA has authority to require owners or operators to provide records or other information in advance of, or in lieu of, an inspection.

This tool provides FDA with:

- Ability to evaluate compliance remotely when on-site inspection is not immediately feasible

- Flexibility to assess specific concerns without conducting a full inspection

- Option to prepare more efficiently for future on-site inspections

While useful, FDA has noted that remote records review is not equivalent to an on-site inspection for surveillance purposes and should be considered a supplementary tool rather than a replacement.

Sampling and Testing

FDA laboratories continue to test drug products for quality, using:

- Testing standards set by the United States Pharmacopeia

- Standards submitted in marketing applications

- Methods developed by FDA

This testing has consistently shown that medicines manufactured in foreign countries that are imported into the United States meet U.S. market quality standards. However, product testing provides information about individual batches rather than overall manufacturing system quality.

Implications for Manufacturers and Regulatory Strategy

Understanding Your Facility’s Risk Profile

Manufacturers can take proactive steps to understand their facility’s likely risk profile under the SSM:

- Self-Assessment Against Risk Factors: Evaluate your facility against each of the SSM risk factors. Consider:

- Product types manufactured and their inherent risks

- Facility operations and complexity

- Patient exposure based on volume and number of products

- Compliance history and any previous inspection findings

- Time since last inspection

- Any hazard signals that may have been reported

- Internal Risk Scoring: While FDA does not publicly disclose the specific weighting of risk factors in the SSM, companies can develop internal quality control scoring systems aligned with the SSM risk factors to better predict conditions FDA may deem high-risk.

- Regional Considerations: For facilities located in countries or regions with known compliance challenges, recognize that this may be a factor in inspection prioritization, even if your individual facility has a strong compliance history.

Maintaining Inspection Readiness

Given that inspection frequency is risk-based rather than fixed, manufacturers should maintain continuous inspection readiness rather than preparing only when an inspection is anticipated:

- Robust Quality Systems: Ensure that quality systems result in a robust state of control and promote a quality culture that exceeds basic CGMP compliance. FDA’s MAPP 5014.1 Rev. 1 emphasizes that CGMP compliance is the floor, and FDA is looking for companies to exceed those standards.

- Proactive Risk Management: Implement comprehensive risk management approaches consistent with ICH Q9 principles, addressing quality risks before they result in hazard signals or compliance issues.

- Data Integrity Controls: Ensure robust data integrity practices consistent with ALCOA+ principles (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available).

- Foreign Facility Considerations: For foreign facilities, be prepared for potentially preannounced inspections but recognize that FDA is moving toward more unannounced inspections. Maintain readiness at all times.

Responding to Increased Scrutiny

Facilities that recognize they may be high-priority targets for inspection based on their risk profile should:

- Conduct Internal Assessments: Perform comprehensive self-inspections or engage external consultants to conduct mock FDA inspections.

- Address Known Gaps: Proactively remediate any known gaps in compliance, particularly those involving data integrity, process controls, or quality unit oversight.

- Prepare Documentation: Ensure that all required documentation is complete, well-organized, and readily accessible to inspectors.

- Training and Communication: Train facility personnel on inspection procedures, proper communication with investigators, and handling of inspection-related requests.

Strategic Considerations for Foreign Facilities

Foreign manufacturers face additional considerations:

- Understanding Preannouncement Implications: While advance notice of inspections has been standard practice, recognize that FDA is working to expand unannounced foreign inspections. Continuous compliance is essential.

- Translation Capabilities: Consider developing independent translation capabilities or relationships with professional translation services, as FDA is moving away from establishment-provided translators.

- Travel and Accommodation Protocols: Be prepared for FDA investigators to decline establishment-provided accommodations and travel arrangements as FDA works to enhance inspection independence.

- Rapid Response Capabilities: Given potential language and time zone barriers, establish protocols for rapid response to FDA information requests and post-inspection follow-up.

Conclusion

The FDA’s risk-based approach to site selection for routine surveillance inspections represents a significant evolution from the previous fixed-interval inspection model. The Site Selection Model, originally implemented in 2005 and codified in law through FDASIA in 2012, enables FDA to allocate limited inspection resources based on scientifically sound risk assessment.

The eight primary risk factors—inherent product risk, facility type, patient exposure, compliance history, time since last inspection, hazard signals, foreign regulatory authority inspectional history, and regional compliance patterns—provide a comprehensive framework for assessing the public health risk associated with each manufacturing facility. This approach promotes parity between domestic and foreign facilities while ensuring that higher-risk sites receive appropriate regulatory attention.

The shift toward increased foreign inspections since FY2015 reflects the globalized nature of pharmaceutical manufacturing and FDA’s commitment to protecting the U.S. drug supply regardless of where products are manufactured. However, this shift has revealed persistent challenges including staffing shortages, the inspection backlog created by the COVID-19 pandemic, and questions about the equivalence of preannounced foreign inspections to unannounced domestic inspections.

Recent policy developments, including the May 2025 executive order, planned pilot programs for unannounced foreign inspections and independent translation services, and the addition of regional compliance history as a risk factor, signal FDA’s ongoing efforts to enhance the rigor and effectiveness of its foreign inspection program.

For manufacturers, understanding the SSM’s risk factors and maintaining continuous inspection readiness are essential components of regulatory compliance strategy. Whether a facility is inspected every two years or at longer intervals depends on its risk profile—not on any predetermined schedule. The key to successful regulatory management lies in implementing robust quality systems that consistently exceed basic CGMP requirements, proactively managing risks, and maintaining the documentation and practices necessary to demonstrate compliance at any time.

As the pharmaceutical manufacturing landscape continues to evolve, the FDA’s risk-based approach to inspection prioritization will remain a cornerstone of drug quality oversight. Manufacturers that align their quality systems and compliance strategies with the principles underlying the SSM will be best positioned to meet regulatory expectations and ensure patient safety.

Key References

- FDA MAPP 5014.1 (September 2018): Understanding CDER’s Risk-Based Site Selection Model

- FDA MAPP 5014.1 Rev. 1 (July 2023): Understanding CDER’s Risk-Based Site Selection Model (Revised)

- Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) of 2012, Public Law 112-144

- Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022 (FDORA), title III of Division FF of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, Public Law 117-328

- Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, section 510(h) and section 704

- FDA Compliance Program 7356.002 — Drug Quality Assurance

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) Reports on FDA Foreign Drug Inspection Program (GAO-17-143, GAO-20-262T, GAO-22-103611)

- FDA Congressional Testimony: Securing the U.S. Drug Supply Chain (December 10, 2019)

- FDA Congressional Testimony: COVID-19 and Beyond: Oversight of FDA’s Foreign Drug Manufacturing Inspection Process (June 2, 2020)

Table 1: Evolution of FDA Inspection Requirements

| Time Period | Statutory Requirement | Practical Implementation | Key Legislation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-2005 | Biennial inspection for domestic drug establishments | Fixed-interval inspections, primarily domestic focus | FD&C Act section 510(h) (original) |

| 2005-2012 | Biennial requirement still in statute | Risk-based SSM implemented as policy, but biennial requirement remained law | SSM introduced via “Pharmaceutical Quality for the 21st Century” initiative |

| 2012-Present | Risk-based inspection schedule mandated by law | SSM formally authorized and implemented for all sites regardless of location | FDASIA (2012), FDARA (2017), FDORA (2022) |

Table 2: SSM Risk Factors Comparison (2018 vs. 2023)

| Risk Factor Category | MAPP 5014.1 (2018) | MAPP 5014.1 Rev. 1 (2023) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site type | Included | Included | No change |

| Time since last inspection | Included | Included | No change |

| FDA compliance history | Included | Included | No change |

| Foreign regulatory authority inspection history | Included | Included | No change |

| Patient exposure | Included | Included | No change |

| Hazard signals | Included | Included | No change |

| Inherent product risk (8 sub-factors) | Included | Included | No change |

| Regional/country compliance history | Not included | Added | New in 2023 |

Table 3: Foreign vs. Domestic Drug Inspections (Selected Fiscal Years)

| Fiscal Year | Domestic Inspections | Foreign Inspections | Total | Foreign % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY2012 | ~3,100 | ~1,200 | ~4,300 | 28% |

| FY2015 | ~2,800 | ~2,900 | ~5,700 | 51% |

| FY2016 | ~3,200 | ~3,400 | ~6,600 | 52% |

| FY2018 | ~2,800 | ~3,000 | ~5,800 | 52% |

| FY2019 | ~2,900 | ~3,200 | ~6,100 | 52% |

| FY2020 | ~1,600 | ~600 | ~2,200 | 27% |

Note: FY2020 numbers reflect the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to suspension of most inspections beginning in March 2020.

Table 4: Top Countries for Foreign Drug Manufacturing Establishments (as of 2024)

| Rank | Country | Number of Establishments | Primary Product Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | India | ~3,000+ | APIs and finished dosage forms |

| 2 | China | ~2,000+ | APIs and finished dosage forms |

| 3 | Germany | ~500+ | APIs and finished dosage forms |

| 4 | Italy | ~400+ | APIs and finished dosage forms |

| 5 | United Kingdom | ~350+ | Finished dosage forms |

| 6 | Canada | ~300+ | Finished dosage forms |

| 7 | Japan | ~250+ | APIs and biologics |

| 8 | France | ~250+ | Finished dosage forms |

| 9 | Ireland | ~200+ | Finished dosage forms and biologics |

| 10 | Switzerland | ~200+ | APIs and finished dosage forms |

Note: These figures are approximate and represent establishments manufacturing drugs for the U.S. market. The actual numbers fluctuate as new establishments register and others cease operations.

related product

[blogcard url=https://ecompliance.jp/qms-md/ title=”QMS(手順書)ひな形 医療機器関連” ] [blogcard url= https://ecompliance.co.jp/SHOP/L_FDA.html title=”【VOD】FDA査察対応セミナー・入門編”] [blogcard url= https://ecompliance.co.jp/SHOP/L_CAPA.html title=”【VOD】製薬企業・医療機器企業におけるFDAが要求するCAPA導入の留意点”] [blogcard url= https://ecompliance.co.jp/SHOP/BOOK-FDA1.html title=”【書籍】FDA査察対応”] [blogcard url= https://ecompliance.co.jp/SHOP/P109.html title=”【書籍】 3極GCP査察の指摘事例/対応と FDA,EMAの特徴的な要求事項対策”]Related Articles

- Understanding Part 11 in FDA Inspections: Key Considerations for Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Companies

- Which Companies Are Subject to FDA Inspection?

- Inspection Site Selection Through the Site Selection Model (SSM)

- Have Part 11 Inspections Disappeared? Understanding Current Regulatory Trends

- Lack of Management Understanding and IT Department Resistance: Key Challenges for Japanese Companies

- Understanding the “15-Minute Rule” in FDA Inspections: An Industry Best Practice

Comment