The Importance of Usability: Lessons from Aviation Accidents

Pursuing the latest technology and optimizing performance is undoubtedly important. However, equally essential is the perspective of usability—ensuring that users can actually operate these technologies and interpret them correctly. This aspect must never be overlooked in product and system design.

Pursuing the latest technology and optimizing performance is undoubtedly important. However, equally essential is the perspective of usability—ensurin…

What is Usability?

Usability fundamentally refers to the characteristics of being “easy to use,” “easy to understand,” and “effective” in products and services. It is a critical factor in evaluating how efficiently and safely a product or system can be utilized by its users. In domains where human safety and decision-making are directly at stake—such as medical devices, aviation systems, and software applications—the absence of adequate usability can lead to catastrophic accidents with potentially fatal consequences.

The Nagoya Airport Accident: A Case Study in Usability Failure

To illustrate the critical importance of usability, we examine the crash of a China Airlines aircraft at Nagoya Airport on August 7, 1994. This accident is still referenced today as a significant lesson in human factors engineering and system design, highlighting the dangers that arise when a gap emerges between an aircraft’s operational interface and pilot understanding.

Background of the Accident

The accident aircraft was an Airbus A300-622R, a structurally sound aircraft equipped with the latest automated flight control systems. However, the sequence of events leading to the accident revealed a fundamental failure in shared understanding between the pilot and the system regarding its operational status and procedures.

Specifically, during the process of attempting to restore the autopilot (automatic pilot) function, the pilot was unable to accurately ascertain the system’s state. The autopilot restoration procedure on Airbus aircraft differs significantly from that on Boeing aircraft. When pilots who are unfamiliar with these procedural differences operate across different aircraft types, the consequences can be catastrophic.

Differences in Cockpit Interface Design

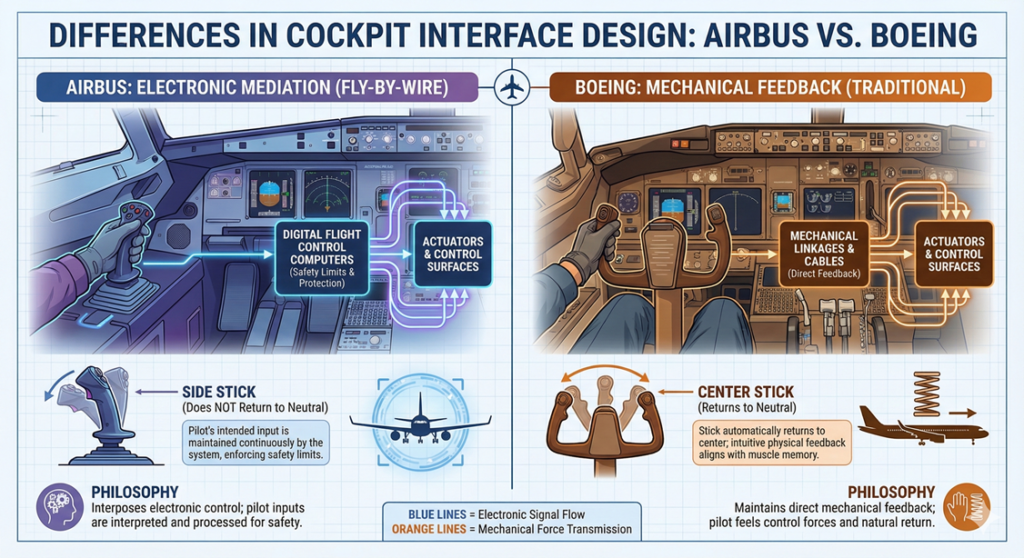

Airbus and Boeing employ fundamentally different design philosophies in their approach to aircraft control.

Airbus, through its adoption of the fly-by-wire electronic flight control system, interposes electronic control mediation between the pilot’s inputs and actual aircraft control. In this system, the pilot’s commands are interpreted and processed by electronic controllers designed to prevent unsafe control inputs by enforcing safety limits. The side stick (control column) does not automatically return to neutral position; instead, it maintains the pilot’s intended input continuously.

Boeing has historically maintained a more traditional mechanical feedback approach, with a center stick (control column) that returns to neutral position. This design provides more intuitive physical feedback: when the pilot releases the control, the stick automatically returns to center, and the aircraft naturally tends to return to level flight—a process that aligns with pilot intuition and muscle memory developed across conventional aircraft.

Analysis from a Usability Perspective

These differences represent far more than mere technical choices; they profoundly influence pilot cognitive load and the difficulty of maintaining accurate system awareness. The Nagoya Airport accident illuminates the following usability challenges:

- System State Visibility: When different aircraft types employ fundamentally different control philosophies, pilots who lack clear understanding of each system’s operating principles are prone to judgment errors, particularly under high-stress conditions.

- Feedback Mechanisms: When direct physical feedback (such as stick centering) is absent, pilots must rely exclusively on visual indicators and numerical readouts, significantly increasing cognitive burden.

- Standardization and Compatibility: For pilots who operate multiple aircraft types, adequate training, operational procedures, and manuals must account for the differences in control procedures and system response characteristics across all aircraft they fly.

Application of These Lessons to Medical Device Industry

Within the medical device industry, similar usability challenges carry significant consequences. When complex diagnostic equipment, therapeutic devices, and data management systems are deployed in clinical settings, failure by healthcare professionals to accurately understand device functionality and operating principles can lead to diagnostic errors or operational mistakes.

International standards such as ISO 62366-1 (Medical Devices—Usability) and IEC 62304 (Medical Device Software—Lifecycle Processes) mandate that designers analyze user characteristics, use environments, and potential harms, then base design decisions on these findings. Furthermore, with the full implementation of the IVDR (In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation) in 2023, regulatory requirements within the European Union increasingly demand rigorous demonstration of usability in medical device evaluation.

Organizational Paradigm Shift in Design Philosophy

Between 2024 and 2025, many organizations are advancing the implementation of new technologies. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and cloud-based systems certainly offer enhanced functionality and scalability. However, it is not uncommon for organizations to give insufficient consideration to how these technologies will actually be perceived and operated by end users.

A critical point must be emphasized: all of these systems are ultimately operated by human beings. This fundamental fact must not be lost sight of. Whether at the technology development stage or the proof-of-concept phase, meaningful attention to usability is as essential as attention to functionality and performance.

Conclusion

What is required of designers, developers, and organizational leadership is not merely the pursuit of cutting-edge technology, but a deep understanding of who will use the resulting product or system, in what context it will be used, and how they will operate it.

During proof-of-concept experiments and new product planning phases, the focus should not be exclusively on technological capability. Rather, attention must be devoted to usability, ensuring that actual users can safely and effectively achieve the intended purpose of the product or service through its design. This principle is universal across all domains where human life or societal trust is at stake—from aircraft to enterprise software systems to medical devices.

Related Articles

- Attending an FDA Inspection: Lessons from a Zero-Observation Success

- Root Cause Investigation and Recurrence Prevention Are Paramount – Lessons Learned from the JAL Jumbo Jet Crash

- Learning from the History of Quality Culture: The 1972 Dextrose Solution Contamination Incident and Lessons from MHRA

- The Importance of Use Environment and User Characteristics in Medical Device Usability Engineering

- Lessons from the China Airlines Flight 140 Crash: Human Factors and Error Prevention

- Learning from Smartphone Usability: Principles for Medical Device Design

Comment