Why Should We Focus on Differences from Predicated Devices in Medical Device Design?

A Lesson from Design Change Implementation

In 2023, a medical device manufacturer developing a successor model of a ventilator changed only “a few” materials from the predecessor device, yet unexpected problems emerged post-market. Under high humidity conditions, the new material developed fine cracks, causing a loss of airtightness. Although the predecessor had more than 10 years of clinical use experience and had undergone thorough improvement through post-market complaint management, this single material change introduced entirely new risks.

In 2023, a medical device manufacturer developing a successor model of a ventilator changed only “a few” materials from the predecessor device, yet un…

As demonstrated by this case, design difference management from predecessor devices in medical device development is not merely a formal procedure, but a critical operational process for protecting patient safety. This article explains the theoretical foundation and practical application of why we must focus on differences from predecessor devices.

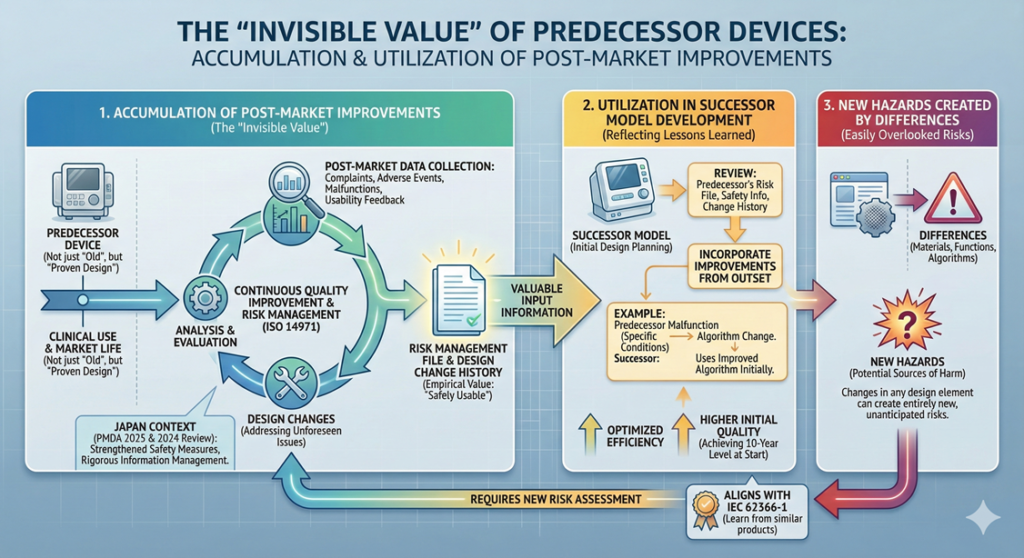

The “Invisible Value” of Predecessor Devices: The Accumulation of Post-Market Improvements

In medical device design, a predecessor device is not simply an “old product.” It represents a “proven design” that has been used in actual clinical settings and has overcome numerous challenges in the market.

Predecessor devices accumulate solutions to problems that could not be foreseen during initial development, embodied as design changes. For example, issues emerging during post-market use—unforeseen conditions not anticipated at initial approval, unexpected reactions in specific patient populations, and feedback from healthcare professionals regarding usability—are addressed through continuous quality improvement implemented after the product reaches the market.

This process is systematically conducted as part of risk management based on ISO 14971. Risk management is a process of identifying, analyzing, evaluating, and appropriately managing risks related to medical devices, and is performed continuously throughout the product lifecycle. Complaint information, adverse event reports, and malfunction information collected post-market are all reflected in the risk management file, and where necessary, result in design changes.

As of 2025, the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) in Japan is strengthening post-market safety measures for medical devices, and manufacturers are increasingly required to implement more rigorous post-market information collection, analysis, and necessary actions. Additionally, the adverse event reporting system for medical devices underwent review in 2024, requiring more rapid and comprehensive information management. Therefore, the design of a predecessor device embodies not only the functional aspect of “operating properly” but also the empirical value of “being safely usable in actual clinical settings.”

Utilization of Predecessor Device Information in Successor Model Development

When developing a successor model, design changes implemented in the predecessor device become extremely valuable input information. This represents a process of reflecting lessons learned by the predecessor in the market into the new product’s specifications.

Specifically, in the initial stages of design development planning, a detailed review is conducted of the predecessor’s risk management file, post-market safety management information, and design change history. For instance, if records show that the predecessor experienced “malfunction under specific use conditions, prompting an algorithm change,” the successor would incorporate the improved algorithm in its initial design.

Through this approach, the successor can achieve the quality level that the predecessor reached after ten years of development from the very outset. By inheriting the predecessor’s “evolution history,” both development efficiency and product quality can be optimized.

IEC 62366-1 (Principles and procedures for the development of medical device software) recommends learning from usage problems in similar products, and the utilization of predecessor information aligns precisely with this philosophy.

New Hazards Created by Differences: Easily Overlooked Risks

Conversely, the very differences from the predecessor device become sources of new hazards. A hazard is a potential source that could cause harm, and changes in any design element—materials, functions, algorithms—can create entirely new hazards.

Examples of Hazards from Material Changes

As demonstrated in the ventilator example introduced at the beginning, material changes may appear minor but can introduce significant risks. Another example involves changing a catheter material to a more flexible polymer. Although biocompatibility testing showed no issues, in actual clinical use, the material degraded when exposed to certain disinfectants—a problem not detected in vitro testing.

The predecessor used a metal stent with well-understood interactions with disinfectants based on years of use experience. However, the new polymer material, with its different properties, required entirely new risk assessment. This example illustrates how material changes can conceal risks not detected by standard in vitro testing like biocompatibility studies.

Examples of Hazards from Feature Addition

In recent years, medical device digitalization has rapidly advanced. As of 2025, many medical devices incorporate IoT functionality and remote monitoring capabilities. For example, consider adding smartphone connectivity to a blood glucose meter that previously operated as a standalone device.

This feature addition creates entirely new hazards that did not exist in the predecessor: Bluetooth communication electromagnetic interference, security risks during data transmission, and display errors from smartphone application bugs. Security risks in particular can directly cause harm through patient data breaches or unauthorized access.

Regarding FDA cybersecurity-related guidance, a draft of “Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions” was published in April 2023, and as of 2025, consultation responses based on this draft content are proceeding. As the final version is being developed, industry comments continue to be addressed. Manufacturers are required to establish cybersecurity risk management systems aligned with the draft content. Additionally, the PMDA has strengthened consultation services regarding medical device cybersecurity, particularly for devices with remote monitoring or cloud connectivity functions, now requiring detailed security threat analysis and countermeasures.

Examples of Hazards from Algorithm Changes

In 2025, with increasing adoption of AI (Artificial Intelligence) and ML (Machine Learning) in medical devices, algorithm changes represent a particularly critical type of difference requiring careful management.

For example, in a medical imaging diagnostic support device, changing from conventional statistical methods to deep learning-based algorithms may improve diagnostic accuracy, yet introduces new risks: the “black box problem” (difficulty explaining decision rationale), performance degradation in specific patient populations due to training data bias, and failures when encountering unexpected input data.

Following the publication of FDA’s AI/ML medical device guidance in 2023 and the announcement of its AI/ML medical Device Action Plan in 2024, FDA continues, as of 2025, to refine regulatory requirements for AI/ML medical devices with continuous learning capabilities. Particularly important is the concept of Performance Monitoring—the ability to continuously assess how device diagnostic accuracy and algorithm performance evolve in the actual post-market environment, with capability to respond as needed.

The PMDA has similarly significantly strengthened consultation services for AI/ML medical devices in 2024, requiring multilayered risk management different from conventional devices: algorithm change management, training data quality assurance, performance verification methods, and continuous learning process management. Notably, algorithm version management and the assessment of safety and efficacy impacts from algorithm changes have become core concepts in future AI/ML medical device regulation.

Why We Must Not Simply Copy “Approved Design”

Medical device approval submissions contain detailed design information current at that point in time. However, simply copying this approved-time design when developing a successor represents a critical error.

The reason is that between product approval and successor development, numerous design changes may have been implemented in the predecessor device. These changes exist in various forms—some as minor modifications reported through notification procedures, some through formal amendments, and some as manufacturing quality improvements.

The Reality of Design Change Management

Consider an example: suppose an infusion pump was approved in 2015 and remained on the market through 2025—10 years—during which the following design changes were implemented.

In the first year, complaints emerged regarding air bubble entrainment during drug aspiration for specific vial geometries, prompting a change to the aspiration mechanism. In year three, performance degradation was reported when used in high-temperature environments, leading to conversion to a heat-resistant motor. In year five, following updates to international electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) testing standards, a noise filter circuit was added. In year eight, responding to user interface improvement requests, display screen contrast was enhanced.

Each of these changes represented important improvements based on insights gained from actual post-market use experience. If the successor’s developer referenced only the 2015 approval documents and copied that design, none of these ten years of improvements would be reflected, resulting in a product that reintroduces already-solved problems.

Current Design Information Management System

Under the Quality Management System (QMS) regulation, design management requires recording and management of design changes. Specifically, all design changes and their rationale must be documented in the Design History File (DHF).

When developing a successor model, consulting the predecessor’s latest DHF and obtaining the actual design information of currently manufactured products is essential. This requires close coordination with manufacturing departments, since the manufacturing floor sometimes implements substantive process improvements or component changes without formal design change procedures.

As of 2025, many medical device manufacturers have implemented PLM (Product Lifecycle Management) or PDM (Product Data Management) systems, enabling centralized design information management and history tracing. While these systems facilitate access to “accurate design information for currently manufactured products,” close communication among relevant departments remains indispensable. Additionally, understanding the risk assessments and clinical background underlying design changes becomes important reference material in successor development.

Regulatory Requirements: An International Perspective

The US FDA Approach

In 510(k) submissions, FDA applies the concept of substantial equivalence, but when differences are substantial or when new risks are created, substantial equivalence may not be recognized, potentially requiring the more stringent Premarket Approval (PMA) pathway.

As of 2025, FDA continues to evolve regulation of digital health technologies, AI/ML medical devices, and cybersecurity. Difference management in these domains requires special consideration. Particularly regarding digital health technology, the definition and classification of Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) undergoes continuous review. Even for software-only devices, additions of new algorithms or data integration functionality are increasingly recognized as substantial differences.

PMDA’s Current Direction

In Japan, the concept of “identity” holds paramount importance in medical device approval review. For a successor model to maintain identity with its predecessor, differences must remain within defined parameters. When changes transgress identity boundaries, new approval applications become necessary.

The PMDA operates programs such as the Breakthrough Devices Designation Program and Conditional Early Approval Program to promote implementation of innovative medical devices. The relationship between successor and predecessor also becomes important when utilizing these programs. In 2024, PMDA’s consultation strategy underwent renewal, providing significantly enhanced early-stage consultation services for emerging technology-based medical devices including AI/ML devices, remote care devices, and wearable medical devices. Accordingly, clearly organizing differences between successor and predecessor from early development stages and conducting consultations with PMDA as appropriate has become an important practice leading to efficient development and approval acquisition.

The Equivalence Concept in EU MDR

The EU’s medical device regulation (MDR: Medical Device Regulation) applies stricter equivalence evaluation than 510(k) requires. Particularly, evidence of performance and safety equivalence must be presented in detail, including clinical evaluation reports. When technical or clinical differences exist between successor and predecessor, specific evidence demonstrating how these differences affect risk must be presented.

The Culture of Continuous Improvement

Design difference management from predecessor devices is not merely a regulatory compliance procedure. It represents a vital process for applying past lessons to the future and continuously enhancing patient safety.

Respect the lessons learned by the predecessor in the market and apply them to successor models. Simultaneously, humbly recognize new risks created by differences and manage them appropriately. The successor, too, learns from the market and accumulates knowledge for the next generation. This cycle of continuous improvement represents the essence of quality culture in the medical device industry.

As of 2025, medical devices are evolving at unprecedented speed—digitalization, AI adoption, adaptation to personalized medicine. In such an environment, differences from predecessors tend to become increasingly substantial and complex. Precisely because of this trend, the importance of difference management will continue to grow.

Each individual involved in development should understand the fundamental nature of the question “Why must we focus on differences from predecessor devices?” and maintain an unwavering commitment to patient safety as paramount. This commitment becomes the driving force in creating excellent medical devices.

Related Articles

- Differences Between Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices

- The Importance of Design Control in Medical Devices

- Differences Between Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Regulations Regarding Engineering Design

- Understanding the Difference Between “Design” and “Design Control” in Medical Devices

- Safe Design of Medical Devices: Understanding Risk Management Fundamentals

- Why FMEA Should Not Be Used for Medical Device Design

Comment