…

From “Validation” to “Verification”: The Evolution of Computer System Assurance in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

Historical Context: GAMP 4 and the Compliance Cost Challenge

In December 2001, the International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE) published GAMP 4, titled “GAMP Guide for Validation of Automated Systems.” This represented a major milestone in the evolution of computerized system validation (CSV) guidance for the pharmaceutical industry. GAMP 4 significantly expanded the scope beyond manufacturing to encompass all GxP-regulated systems, including Good Laboratory Practice, Good Clinical Practice, Good Distribution Practice, and other GxP domains.

GAMP 4 development benefited from substantial regulatory input, with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) participating actively in the review process. This FDA involvement helped establish GAMP 4 as the de facto standard for CSV at that time, providing pharmaceutical companies with a framework that aligned with regulatory expectations.

However, despite its comprehensive approach, GAMP 4 inadvertently created a significant challenge: escalating compliance costs. Under GAMP 4’s framework, pharmaceutical companies often found themselves repeating testing and verification activities that suppliers had already conducted. This double quality assurance approach, while thorough, resulted in duplicative efforts that did not proportionally enhance patient safety or product quality. These compliance costs were ultimately incorporated into product pricing, placing an additional financial burden on patients and healthcare systems.

The FDA’s 21st Century Initiative and ASTM E2500

Recognizing the need for a more efficient approach, the FDA launched its “Pharmaceutical cGMPs for the 21st Century—A Risk-Based Approach” initiative in the early 2000s. This initiative emphasized science-based risk management and sought to modernize pharmaceutical manufacturing quality systems.

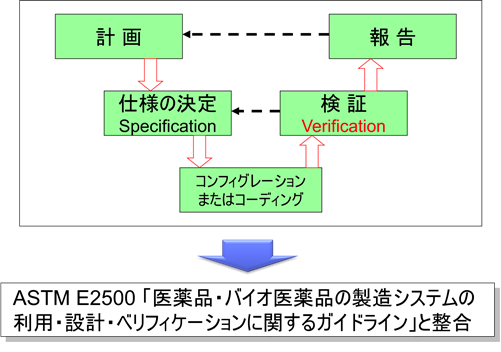

To support this initiative, the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM)—an independent standards organization with global reach and no direct ties to the pharmaceutical industry—developed ASTM E2500. This standard, formally titled “Standard Guide for Specification, Design, and Verification of Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing Systems and Equipment,” was approved in May 2007 and published in June 2007 (subsequently reapproved in 2012 and 2020, with a significant revision published as ASTM E2500-25 in October 2025 to align with FDA’s finalized CSA guidance and ICH Q12).

ASTM develops test methods, standards, and specifications across numerous industries. With members in over 100 countries, ASTM standards are utilized worldwide by companies and government agencies to ensure product safety, quality, and performance. The FDA actively participated in and supported the development of ASTM E2500, though it was not a direct commission but rather a collaborative effort aligned with FDA’s modernization goals.

ASTM E2500 introduced several transformative concepts that would reshape pharmaceutical equipment qualification:

- Terminology Shift: Traditional sequential commissioning and qualification activities (IQ/OQ/PQ) were consolidated under the unified term “verification”

- Risk-Based Approach: Verification activities became scalable based on assessed risk rather than following rigid, prescriptive sequences

- Supplier Leverage: Emphasized utilizing supplier expertise and documentation to avoid duplication

- Subject Matter Experts (SMEs): Elevated the role of knowledgeable SMEs in defining appropriate verification strategies

- Good Engineering Practices (GEP): Integrated engineering activities with quality assurance from project inception

The most recent revision, ASTM E2500-25 (published October 2025), represents a strategic alignment with FDA’s finalized CSA guidance. This revision explicitly incorporates CSA principles and terminology, strengthens connections to ICH Q12 lifecycle management concepts, and provides updated examples reflecting modern manufacturing technologies including continuous manufacturing and advanced process control systems. This harmonization ensures that organizations implementing ASTM E2500 approaches are fully aligned with current FDA expectations.

GAMP 5: Harmonization and Risk-Based Transformation

In 2008, ISPE published GAMP 5, titled “A Risk-Based Approach to Compliant GxP Computerized Systems.” This publication marked a watershed moment in CSV guidance evolution. Most significantly, the word “Validation” disappeared from the title—a deliberate linguistic shift that reflected fundamental philosophical changes in the approach to computerized system assurance.

GAMP 5 was explicitly harmonized with ASTM E2500, as documented in Appendix S1 (“Alignment with ASTM E2500”) of the guide. Key changes included:

Terminology Evolution

While GAMP 4 used “Validation” prominently in its title and framework, GAMP 5 adopted “Verification” to describe testing activities throughout the system lifecycle. This terminology shift had important implications:

- Validation became reserved for the overall process of demonstrating fitness for intended use

- Verification described specific testing activities conducted throughout development and implementation

- This distinction enabled more flexible, iterative approaches rather than treating validation as a distinct post-development phase

The V-Model Reinterpreted

Both GAMP 4 and GAMP 5 reference the V-model (a graphical representation mapping specification phases to corresponding verification phases), but with fundamentally different interpretations:

GAMP 4 V-Model:

- Prescriptive, linear progression

- Heavy emphasis on comprehensive documentation at each phase

- Validation positioned as final verification stage

GAMP 5 V-Model:

- Flexible, adaptable framework

- Verification activities integrated throughout lifecycle

- Terminology adapted to context and methodology

- Supports both traditional waterfall and iterative development approaches

Eliminating Duplicate Efforts

GAMP 5’s harmonization with ASTM E2500 fundamentally changed how pharmaceutical companies approached supplier activities. Instead of pharmaceutical companies repeating all supplier testing as “validation,” GAMP 5 advocated:

- Leveraging supplier development and testing documentation

- Conducting supplier assessments to establish confidence

- Performing verification activities focused on intended use and GxP requirements

- Avoiding unnecessary duplication while maintaining assurance

This approach directly addressed GAMP 4’s compliance cost challenge by preventing wasteful duplication between suppliers and pharmaceutical companies.

Translation Nuances: Japanese vs. English Terminology

An important but often overlooked aspect of this evolution involves language translation. In the Japanese translation of GAMP 5, both verification activities and the overall validation concept are rendered using validation terminology (検証/バリデーション), making the subtle but significant terminology distinction less apparent to Japanese-speaking practitioners. This translation approach, while linguistically reasonable, may have obscured the philosophical shift for many Japanese pharmaceutical companies.

Consequently, some Japanese companies continued implementing rigid GAMP 4-style validation activities even after GAMP 5’s publication, unaware that the international community had evolved toward more flexible, risk-based verification approaches. This illustrates how terminology and translation choices can significantly impact regulatory understanding and implementation across different markets.

GAMP 5 Second Edition (2022): Modernization for Digital Transformation

After 14 years, ISPE published the GAMP 5 Second Edition in July 2022. Rather than issuing “GAMP 6,” ISPE maintained the GAMP 5 designation while significantly updating content to reflect modern technology landscapes and regulatory expectations. The Second Edition represents the industry’s response to rapid digital transformation while maintaining the fundamental risk-based principles established in 2008.

Key Updates in the Second Edition

1. Critical Thinking Emphasis

- New Appendix M12 dedicated to critical thinking principles

- Emphasis on SME judgment over prescriptive compliance

- Focus on “fitness for intended use” rather than exhaustive documentation

- Integration of critical thinking throughout the lifecycle

2. Agile and Iterative Development Support

- Explicit recognition that GAMP framework supports both linear (V-model) and iterative/agile methodologies

- Guidance on applying lifecycle phases in agile projects

- Acknowledgment that user requirements and functional specifications can evolve iteratively

- Support for DevOps and continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) practices

3. Cloud Computing and Service Providers

- New Appendix M11 on IT Infrastructure

- Comprehensive guidance on Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS), and Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS)

- Service provider assessment and management strategies

- Shared responsibility models for cloud services

4. Emerging Technologies

- New Appendix D11 on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML)

- New Appendix D10 on Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technologies

- Guidance on validating systems incorporating these advanced technologies

- Risk-based approaches to novel technological capabilities

5. Data Integrity Enhancement

- Strengthened emphasis on data integrity throughout all appendices

- Explicit alignment with ALCOA+ principles (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, Available)

- Integration with ISPE’s Data Integrity by Design guidance

- Focus on patient safety, product quality, and data integrity over mere compliance

6. Automation and Tools

- New section on “Using Tools and Automation” in Chapter 8 (Efficiency Improvements)

- Recognition that software tools used in validation processes themselves may require classification

- Guidance on leveraging automated testing, continuous monitoring, and system-generated evidence

Alignment with Regulatory Modernization

The GAMP 5 Second Edition explicitly acknowledges and aligns with several regulatory developments:

- ICH Q12 (Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management)

- FDA Quality Management System Regulation (QMSR) alignment with ISO 13485:2016 (effective February 2026 for medical devices)

- FDA Computer Software Assurance (CSA) guidance principles

- EU GMP Annex 11 (Computerised Systems) revisions

- PIC/S data integrity guidance

FDA Computer Software Assurance (CSA): The Latest Paradigm Shift

On September 24, 2025, the FDA finalized its groundbreaking guidance titled “Computer Software Assurance for Production and Quality System Software.” This guidance represents the most significant regulatory development in CSV since GAMP 5’s original publication, formally transitioning the industry from Computer System Validation (CSV) to Computer Software Assurance (CSA).

Core CSA Principles

1. Risk-Based Classification The CSA guidance introduces a binary risk classification:

- High Process Risk: Software functions that, if they fail or perform incorrectly, could directly impact product quality or patient safety

- Not High Process Risk: All other functions

This classification determines the appropriate level of assurance activities, enabling organizations to focus resources where risks are greatest.

2. Flexible Assurance Methods Unlike traditional CSV’s prescriptive testing requirements, CSA explicitly endorses multiple assurance approaches:

| Assurance Method | Appropriate Context | Documentation Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Scripted Testing | High process risk functions; complex workflows; regulatory critical processes | Detailed test protocols, expected results, actual results, pass/fail criteria, traceability matrices |

| Unscripted/Exploratory Testing | Moderate risk functions; user interface validation; scenario-based evaluation | Test objectives, scope, findings, risk assessment, conclusions |

| Automated Testing | Regression testing; continuous integration/deployment; repetitive validations | Test scripts/code, execution logs, results summary, version control |

| Continuous Monitoring | Production systems; ongoing assurance; real-time verification | Monitoring parameters, thresholds, alerts, trending data, periodic reviews |

| Vendor/Developer Evidence | Commercial off-the-shelf software; well-established suppliers | Supplier development documentation, testing evidence, certifications, supplier assessments |

3. Leveraging Supplier Documentation CSA strongly encourages pharmaceutical companies to leverage supplier-provided evidence, including:

- Software development lifecycle (SDLC) documentation

- Supplier validation packages and test results

- Third-party certifications (e.g., SOC 2, ISO 27001)

- Infrastructure certifications for cloud service providers

- Change management and release documentation

This approach directly builds upon GAMP 5 and ASTM E2500 principles, further reducing unnecessary duplication.

4. Cloud Services Explicit Recognition The CSA guidance provides detailed guidance for cloud-based systems:

- Service agreements should address security, data integrity, change management, and disaster recovery

- Automatic updates must be assessed through risk-based assurance when they affect intended use

- Shared responsibility models clearly delineated between service providers and regulated companies

- Infrastructure qualification can leverage provider certifications and attestations

5. Documentation Modernization CSA promotes digital-first recordkeeping:

- System-generated logs and audit trails as primary evidence

- Risk assessments documenting rationale for assurance approach

- Objective evidence demonstrating software performs as intended

- Minimization of redundant documentation that adds no value

CSA Impact on Industry Practice

The finalization of CSA guidance has profound implications:

Efficiency Gains: Organizations can potentially reduce validation documentation by 30-50% by focusing on truly critical functions and leveraging supplier evidence.

Innovation Enablement: The flexible framework removes barriers to adopting modern technologies like AI/ML, cloud computing, and continuous deployment.

Regulatory Alignment: CSA aligns with the upcoming Quality Management System Regulation (QMSR) that harmonizes medical device requirements with ISO 13485:2016 (effective February 2026).

International Harmonization: While FDA-focused, CSA principles align with global regulatory trends toward risk-based, science-driven approaches.

Current State: Ongoing Evolution

As of 2025, the pharmaceutical industry finds itself in a transition period with multiple frameworks coexisting:

Regulatory Landscape

| Region/Authority | Primary Framework | Key Documents | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States (FDA) | Computer Software Assurance | CSA Guidance (September 2025); 21 CFR Part 11 | CSA now official guidance; Part 11 enforcement discretion continues for certain elements |

| Europe (EMA/PIC/S) | Annex 11 Computerised Systems | EU GMP Annex 11; PIC/S PI 011 | Under revision to strengthen data integrity and lifecycle requirements (expected 2026) |

| International | ICH Q10/ISO 13485 | ICH Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System); ISO 13485:2016 (Medical Devices) | Increasing convergence; QMSR harmonization underway |

| Industry Standards | GAMP 5 Second Edition; ASTM E2500 | ISPE GAMP 5 (July 2022); ASTM E2500-25 (October 2025) | Harmonized frameworks supporting risk-based approaches; latest ASTM revision explicitly aligned with CSA |

Implementation Challenges

Despite clear regulatory direction, implementation challenges persist:

1. Cultural Resistance: Organizations accustomed to prescriptive CSV may struggle transitioning to judgment-based CSA approaches. The traditional “check-the-box” mentality, while providing psychological comfort, must give way to critical thinking and risk assessment.

2. Training Gaps: Many validation professionals were trained in traditional CSV methods. Developing competencies in risk assessment, critical thinking, and modern software development methodologies requires significant investment.

3. Documentation Templates: Industry historically relied on standardized validation templates. CSA requires organizations to develop flexible, risk-commensurate documentation that may vary significantly between systems.

4. Supplier Maturity Variability: Leveraging supplier evidence requires suppliers to have robust quality systems and documentation. Supplier maturity varies widely, requiring pharmaceutical companies to conduct thorough assessments.

5. International Harmonization Gaps: While regulatory philosophies are converging, specific requirements differ between regions. Multinational companies must navigate multiple frameworks simultaneously.

6. Legacy System Challenge: Many pharmaceutical facilities operate legacy systems validated under older frameworks. Determining when and how to modernize these validations represents a significant undertaking.

Practical Implications for Industry

For Quality Assurance Professionals

Modern computerized system assurance requires:

- Deep Process Understanding: QA professionals must understand both the system and the underlying manufacturing process to conduct meaningful risk assessments

- Risk Management Expertise: Proficiency in ICH Q9 quality risk management principles and their application to computerized systems

- Critical Thinking Skills: Ability to distinguish between activities that add value versus those performed merely for compliance appearance

- Supplier Management: Competence in assessing and leveraging supplier quality systems and documentation

- Technology Literacy: Basic understanding of software development, cloud computing, and emerging technologies

For System Suppliers

Suppliers play an increasingly critical role:

- Quality System Documentation: Maintaining comprehensive SDLC documentation that customers can review and leverage

- Validation Packages: Providing well-structured validation packages that meet diverse customer requirements

- Change Management Transparency: Clear communication of software changes, updates, and their GxP implications

- Certifications: Obtaining and maintaining relevant third-party certifications (e.g., ISO 27001, SOC 2 Type II)

- GxP Awareness: Understanding pharmaceutical quality system requirements and how products support compliance

For Organizations Implementing Systems

Successful modern system implementation requires:

1. Risk Assessment Rigor: Thorough, documented risk assessments that clearly identify high process risk functions and justify assurance approaches.

2. Supplier Collaboration: Early engagement with suppliers to understand their quality systems, validation packages, and available documentation.

3. Flexible Validation Strategies: Developing system-specific validation strategies rather than applying one-size-fits-all approaches.

4. Documentation Right-Sizing: Creating documentation proportionate to risk—comprehensive for critical functions, streamlined for low-risk elements.

5. Continuous Improvement: Treating system assurance as an ongoing lifecycle activity rather than a one-time event.

6. Cross-Functional Teams: Engaging SMEs from quality, IT, operations, and engineering throughout the lifecycle.

Comparing Traditional CSV vs. Modern CSA

To illustrate the practical differences, consider a typical manufacturing execution system (MES):

Traditional CSV Approach (GAMP 4 Era)

- Extensive user requirements specification (URS) covering every system function (500+ pages)

- Detailed functional specifications for all features

- Comprehensive installation qualification (IQ) testing every installation parameter

- Exhaustive operational qualification (OQ) testing all system functions regardless of GxP impact

- Performance qualification (PQ) in production environment

- Complete traceability matrices linking every requirement to test

- Minimal leveraging of supplier validation evidence

- Timeline: 12-18 months for medium-complexity system

- Documentation: 2,000-3,000 pages

Modern CSA Approach (GAMP 5 Second Edition + FDA CSA)

- Focused requirements documentation emphasizing GxP-relevant functionality (100-200 pages)

- Risk assessment identifying high process risk functions (10-15% of total functionality)

- Leveraged supplier IQ/OQ evidence for standard functionality

- Targeted scripted testing of high process risk functions

- Unscripted testing for user interface and moderate-risk features

- Continuous monitoring of system performance in production

- Streamlined traceability focusing on critical functions

- Strong reliance on supplier validation packages and certifications

- Timeline: 6-9 months for medium-complexity system

- Documentation: 500-800 pages (plus leveraged supplier documentation)

Both approaches achieve the same ultimate goal—demonstrating the system is fit for intended use—but the modern approach accomplishes this more efficiently by focusing resources on actual risks.

International Perspectives: Japan and Beyond

Japan’s Regulatory Landscape

Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) traditionally followed validation approaches closely aligned with GAMP 4, emphasizing comprehensive documentation and testing. However, recent developments indicate modernization:

- ER/ES Guidelines Update (2020): Japan’s Electronic Records/Electronic Signatures guidelines updated to align with international data integrity principles

- ICH Membership: As an ICH founding member, Japan increasingly adopts ICH Q9, Q10, and Q12 principles

- Industry Dialogue: Japanese pharmaceutical companies are gradually adopting risk-based approaches, though often more conservatively than Western counterparts

- Recent PMDA Notifications (2025): PMDA has begun issuing notifications that reference risk-based validation concepts, gradually addressing the terminology gap between Japanese and international guidance, though cultural adoption of these changes remains gradual

The terminology translation challenge mentioned earlier remains relevant but is slowly being addressed. Japanese validation professionals must navigate both Japanese regulatory documents and English-language GAMP/FDA guidance, requiring careful attention to subtle terminology differences. Recent PMDA communications show increasing alignment with international risk-based terminology, though the practical implementation timeline across the Japanese pharmaceutical industry varies significantly by company size and international exposure.

Regulatory Convergence Trends

Despite regional variations, several global trends are evident:

- Risk-Based Focus: All major regulatory authorities now emphasize risk-based approaches over prescriptive requirements

- Data Integrity Priority: ALCOA+ principles universally adopted as foundation for electronic records

- Lifecycle Thinking: Recognition that assurance is continuous throughout system lifecycle, not a one-time validation event

- Supplier Leverage: Growing acceptance of leveraging supplier quality systems and documentation

- Technology Neutrality: Regulatory frameworks increasingly technology-neutral, supporting innovation

Recommendations for Organizations

Based on the evolution from Validation to Verification to Assurance, organizations should:

Immediate Actions (0-6 months)

- Gap Assessment: Evaluate current validation practices against GAMP 5 Second Edition and FDA CSA guidance

- Training Investment: Provide comprehensive training on risk-based validation, critical thinking, and modern assurance methodologies

- Pilot Projects: Identify 1-2 low-complexity systems for pilot CSA implementation

- Supplier Dialogue: Engage key suppliers to understand available validation support and documentation

- Documentation Review: Audit existing validation templates and SOPs for opportunities to streamline

Medium-Term Evolution (6-18 months)

- SOP Revision: Update validation SOPs to incorporate risk-based, flexible approaches aligned with CSA principles

- Risk Assessment Integration: Implement robust risk assessment processes as foundation for all validation activities

- Training Programs: Develop internal training materials and competency assessments for validation staff

- Supplier Qualification: Establish supplier qualification programs enabling reliance on supplier documentation

- Technology Adoption: Begin leveraging automated testing tools, continuous monitoring, and system-generated evidence

Long-Term Transformation (18+ months)

- Cultural Change: Foster organizational culture valuing critical thinking over compliance box-checking

- Legacy System Strategy: Develop phased approach for modernizing legacy system validations

- Center of Excellence: Establish validation center of excellence promoting consistent, efficient practices

- Metrics Development: Implement metrics measuring validation efficiency, effectiveness, and business impact

- Continuous Improvement: Regular review and optimization of validation practices based on lessons learned

Conclusion

The evolution from “Validation” to “Verification” represents far more than terminology change—it reflects fundamental transformation in how the pharmaceutical industry approaches computerized system assurance. This journey, spanning from GAMP 4 (2001) through ASTM E2500 (2007), GAMP 5 (2008), GAMP 5 Second Edition (2022), and FDA CSA guidance (2025), demonstrates regulatory and industry commitment to science-based, risk-driven approaches that better serve patient safety while eliminating wasteful practices.

Key principles emerging from this evolution:

- Risk-Based Prioritization: Focus resources on functions that truly impact patient safety and product quality

- Supplier Collaboration: Leverage supplier expertise and documentation to avoid duplication

- Flexibility: Adapt approaches to system complexity, novelty, and organizational context

- Critical Thinking: Apply judgment and expertise rather than blindly following templates

- Continuous Assurance: Treat system assurance as ongoing lifecycle activity

- Value Focus: Perform activities that genuinely add value, not merely compliance theater

While many Japanese companies and some organizations worldwide continue implementing rigid validation practices inherited from earlier eras, the international regulatory consensus has clearly evolved. Quality assurance remains critically important—indeed, patient safety depends on it—but excessive, duplicative activities that do not enhance safety represent waste that ultimately burdens patients and healthcare systems.

Organizations that successfully navigate this transition will achieve multiple benefits: reduced time-to-market for new systems, lower compliance costs, better resource utilization, enhanced innovation capacity, and ultimately, stronger patient safety through truly risk-based quality assurance.

The pharmaceutical industry stands at an inflection point. The regulatory framework, industry guidance, and technological capabilities necessary for modern, efficient computerized system assurance are now in place. Success requires commitment to change—moving from prescriptive compliance to critical thinking, from rigid validation to flexible assurance, and from individual verification to collaborative quality across the supply chain.

As we look toward the future, emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, blockchain, and continuous manufacturing will require further evolution of validation practices. The principles established through GAMP 5 and FDA CSA provide a solid foundation for addressing these challenges—emphasizing science, risk, and critical thinking over prescriptive rules.

The transformation from Validation to Verification to Assurance is not complete—it is ongoing. Organizations that embrace this evolution will lead the industry toward more efficient, effective, and ultimately safer pharmaceutical manufacturing.

References

- ISPE. (2001). GAMP 4: Guide for Validation of Automated Systems. International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering.

- ASTM International. (2007). E2500-07: Standard Guide for Specification, Design, and Verification of Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing Systems and Equipment. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International.

2a. ASTM International. (2025). E2500-25: Standard Guide for Specification, Design, and Verification of Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing Systems and Equipment. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International.

FDA. (2023). Quality Management System Regulation: Amendments and Quality System Requirements. Federal Register, 88(35):8351-8489.

ISPE. (2008). GAMP 5: A Risk-Based Approach to Compliant GxP Computerized Systems (First Edition). International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering.

ISPE. (2022). GAMP 5: A Risk-Based Approach to Compliant GxP Computerized Systems (Second Edition). International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2025). Computer Software Assurance for Production and Quality System Software: Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

International Conference on Harmonisation. (2005). ICH Q9: Quality Risk Management. Geneva: ICH.

International Conference on Harmonisation. (2008). ICH Q10: Pharmaceutical Quality System. Geneva: ICH.

International Conference on Harmonisation. (2019). ICH Q12: Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management. Geneva: ICH.

ISPE. (2020). GAMP RDI Good Practice Guide: Data Integrity by Design. International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering.

FDA. (2004). Pharmaceutical CGMPs for the 21st Century—A Risk-Based Approach. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

FDA. (2011). Process Validation: General Principles and Practices. Guidance for Industry. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

PIC/S. (2016). PI 041-1: Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity in Regulated GMP/GDP Environments. Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme.

EudraLex. (2011). Annex 11: Computerised Systems. Volume 4, EU Guidelines for Good Manufacturing Practice for Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use.

ISO. (2016). ISO 13485:2016 Medical devices — Quality management systems — Requirements for regulatory purposes. International Organization for Standardization.

related product

[blogcard url=https://ecompliance.jp/qms-md/ title=”QMS(手順書)ひな形 医療機器関連” ] [blogcard url=https://ecompliance.jp/qms-rx/ title=”QMS(手順書)ひな形 医薬品関連” ] [blogcard url= https://ecompliance.co.jp/SHOP/EL-006.html title=”【セミナービデオ】データインテグリティSOP作成セミナー”] [blogcard url= https://ecompliance.co.jp/SHOP/O108.html title=”【VOD】適格性評価とバリデーション”] [blogcard url= https://ecompliance.co.jp/SHOP/P167_EB054a.html title=”【書籍】【追補版】<パーフェクトガイド>経験/査察指摘/根拠文献・規制から導く洗浄・洗浄バリデーション:判断基準と実務ノウハウ【製造現場・QA担当者の質問・課題(Q&A付)】 “] [blogcard url= https://ecompliance.co.jp/SHOP/CSV-5KY-LIVE-00001.html title=”【VOD】CSVセミナー【第1講】”]Related Articles

- From “Validation” to “Verification”: The Evolution of CSV Approaches

- Understanding the Difference Between Validation and Verification

- From CSV to CSA: A Paradigm Shift in Computer System Validation

- The Difference Between Validation and Verification

- Why Validation is Future-Tense While Verification is Past-Tense: Understanding the Temporal Philosophy of Quality Assurance

- Why the V-Model Remains Essential: Evolution from Traditional Validation to Modern Software Assurance

Comment